titanic memorial park cultural landscape inventory

National Mall and Memorial Parks, National Park Service, Washington, DC

Full Text Available: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2288095

Historical Overview

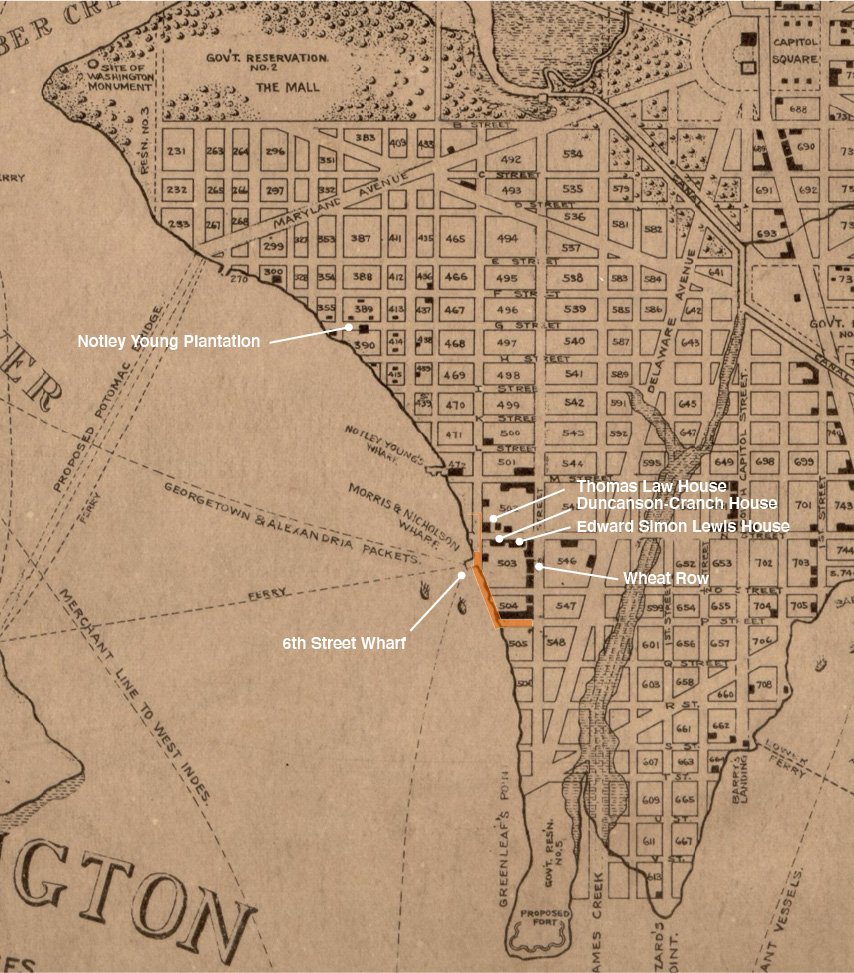

European development began in 1662 when the Young family was issued a 1,000-year lease for Cerne Abbey Manor (Carter et al. 2018: 21-24). The Young family built a plantation in the vicinity of the cultural landscape and cultivated the landing using enslaved labor (Henning 1913: 5; King 1797; King 1796; Priggs 1790). The cultural landscape was almost certainly ceded to federal control under the proprietors’ agreement of 1790, as it would later be planned by L’Enfant and Ellicott as a public right-of-way (Overbeck and Janke 2000: 126-28; McNeil 1991: 47-8; Carter et al. 2018: 249-250). In December 1793, a newly-formed group of real estate speculators, the Greenleaf Syndicate, became the first developers in the southwest quadrant to purchase lots and construct buildings (Brown 1973a; Brown 1973b; Brown 1973c).

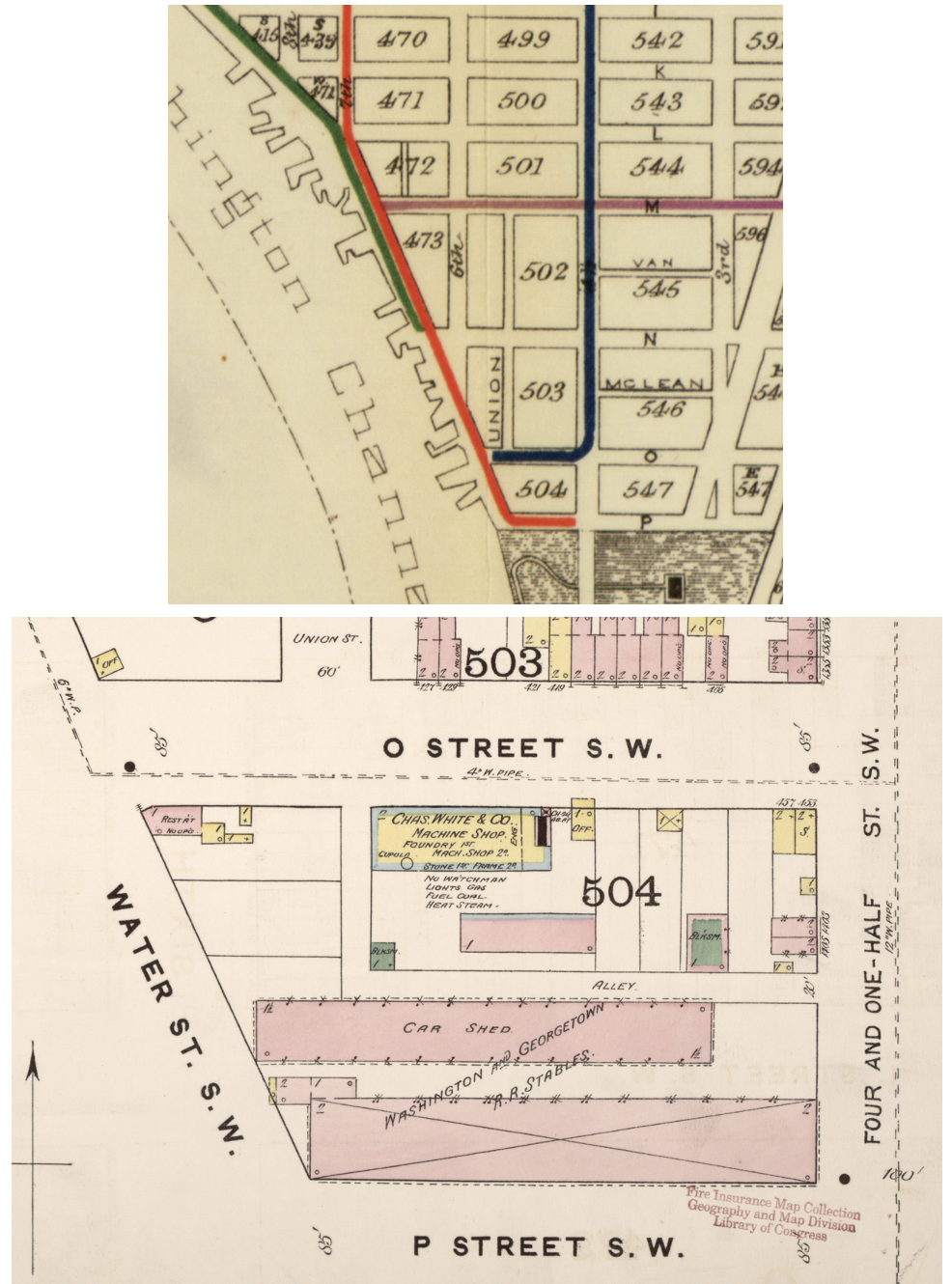

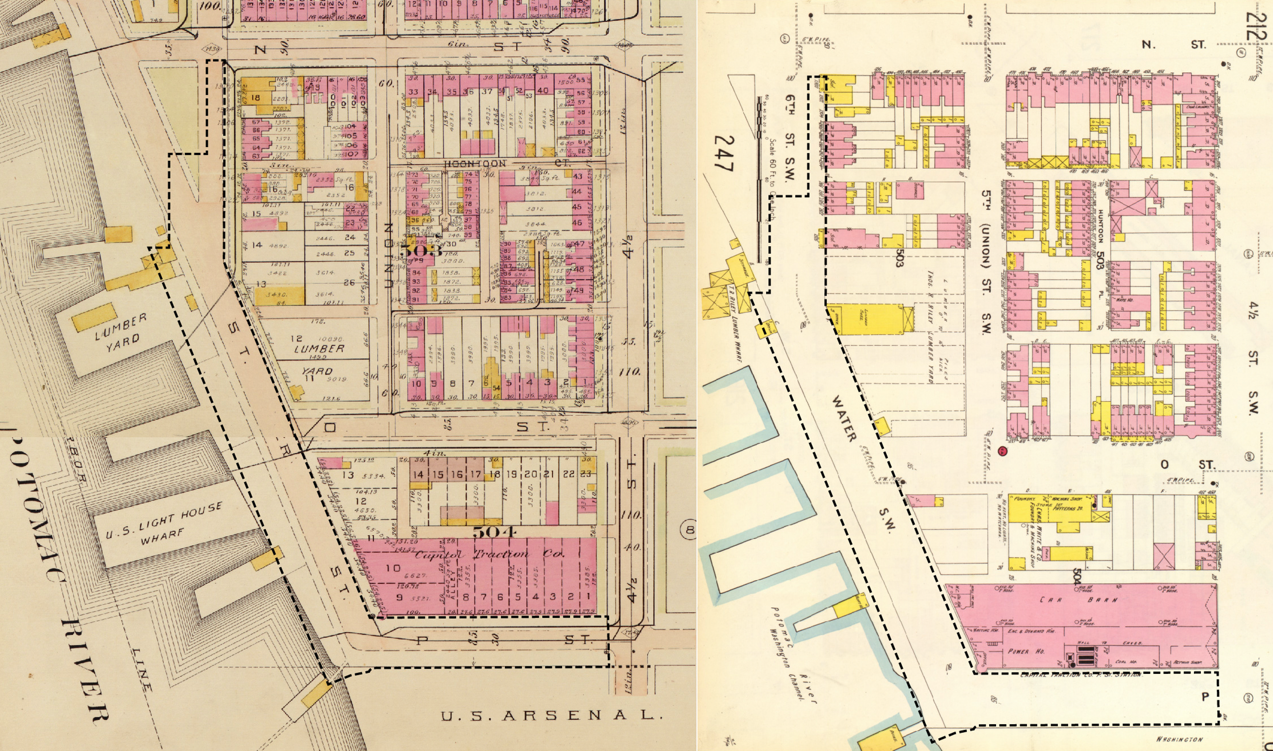

During the Civil War, the cultural landscape served as the city’s main shipping and staging area for Union troops, their armaments, and supplies during the Civil War, owing to its waterfront location and its proximity to the Arsenal. After the Civil War, rapid postwar population growth necessitated the improvement of streets and public lands in the District. In the decades after the conflict, the Territorial Government and later, District of Columbia Board of Commissioners, constructed sewer and road improvements within the study area. As the southwest area of Washington, DC, urbanized in the second half of the 19th century, new streetcar lines began appearing around the city. During this time, tracks were installed in the center of Water Street SW and P Street SW (Trieschmann et al. 2005: 22-26). A significant flood event in 1881 forced Congress to reevaluate and conduct much-needed improvements to the Potomac River—and consequently the southwest waterfront (Gutheim 2006: 94). Construction of the Washington Channel (and later, East Potomac Park) protected the harbor and made it a deep-water port, sheltered from future silting and ice flows (Medler 2010: 92-93). By the early 1900s, much of the area surrounding the cultural landscape had been urbanized. Industrial businesses dotted the larger waterfront lots, and the cultural landscape served as the connective tissue between the various enterprises.

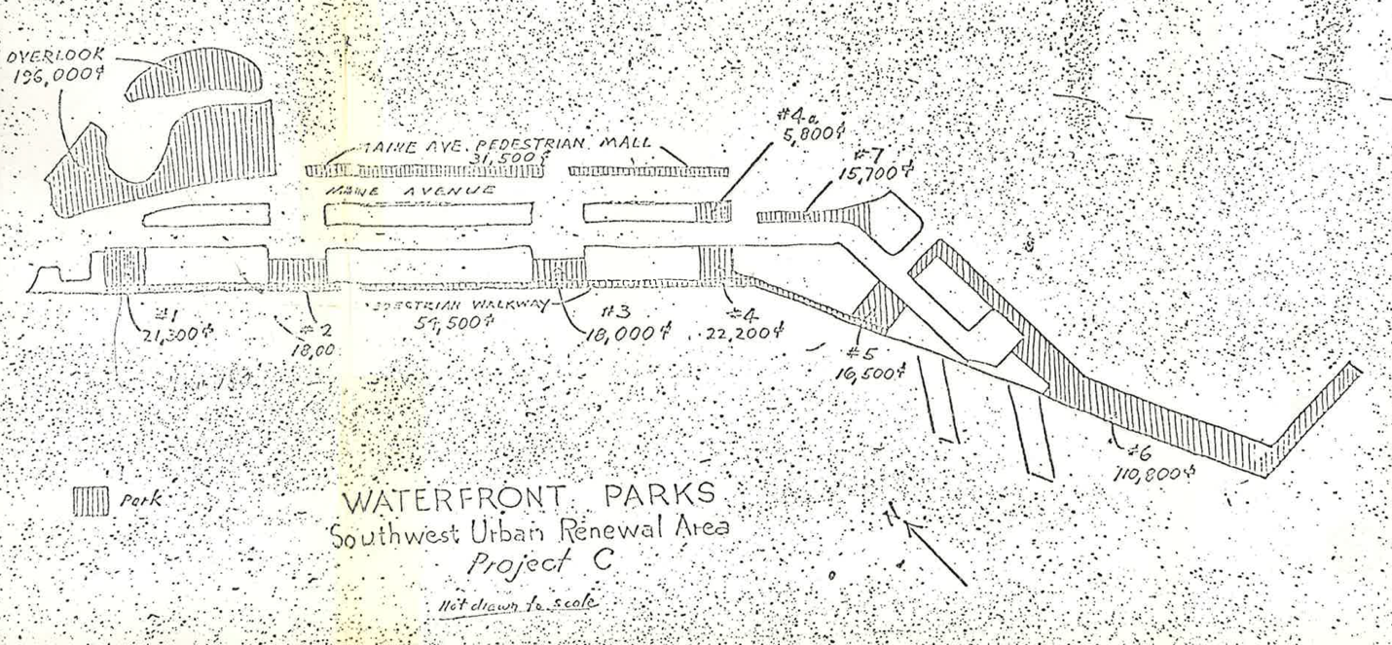

Between 1905 and 1930, the population of Southwest Washington, DC, decreased by a third, dropping from 35,000 to 24,000 residents amid decades of disinvestment. As a result, the Southwest rapidly gained the attention of civic reformers and federal authorities, who viewed the neighborhood as an eyesore and a slum (Smith 1988: 68). By the mid-20th century, calls for the reclamation of the “blighted” Southwest would lead to full-scale clearance and redevelopment, and the displacement of thousands of residents, as part of one of the nation’s earliest and largest urban renewal projects (Ammon 2006:10-17). In 1945, Congress created the Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA) and tasked it with revitalizing “blighted” areas of Washington, DC, through acquisition, clearance, and redistribution of land for redevelopment (Ammon 2009: 182). Redevelopment adjacent to the cultural landscape began in 1954. In 1960, architect Chloethiel Woodward Smith was hired by the Federal City Council to create a separate waterfront redevelopment plan for Project Area C. Her design called for an "urban edge" along the river consisting of a 20’-wide public park and was the impetus for the later development of the cultural landscape as a waterfront park (Ammon 2004: 95-96).

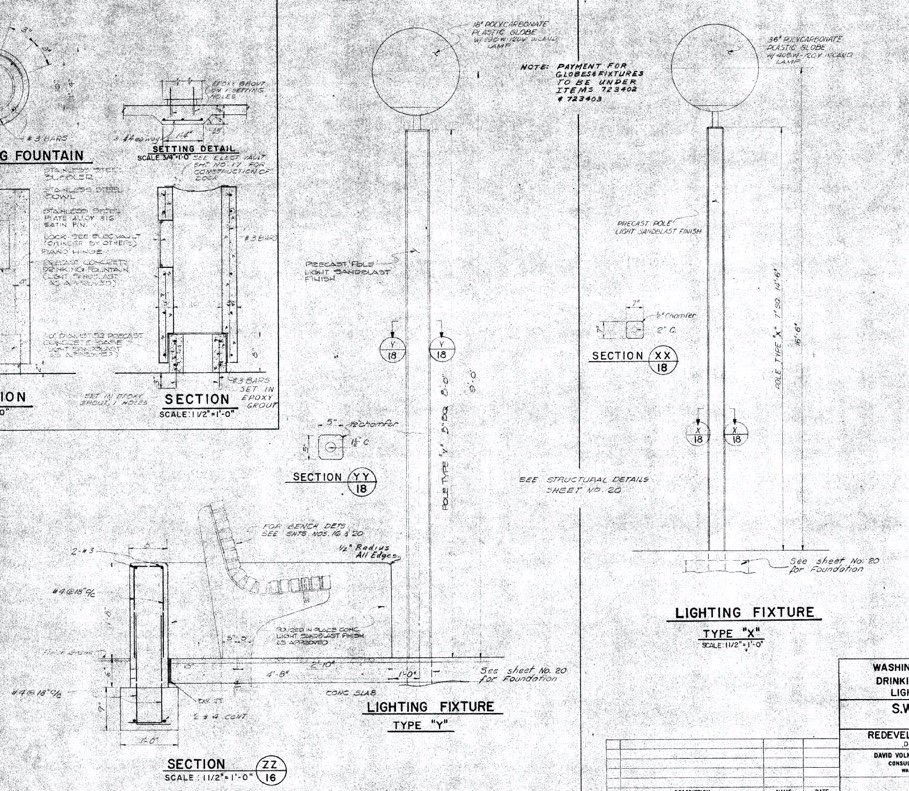

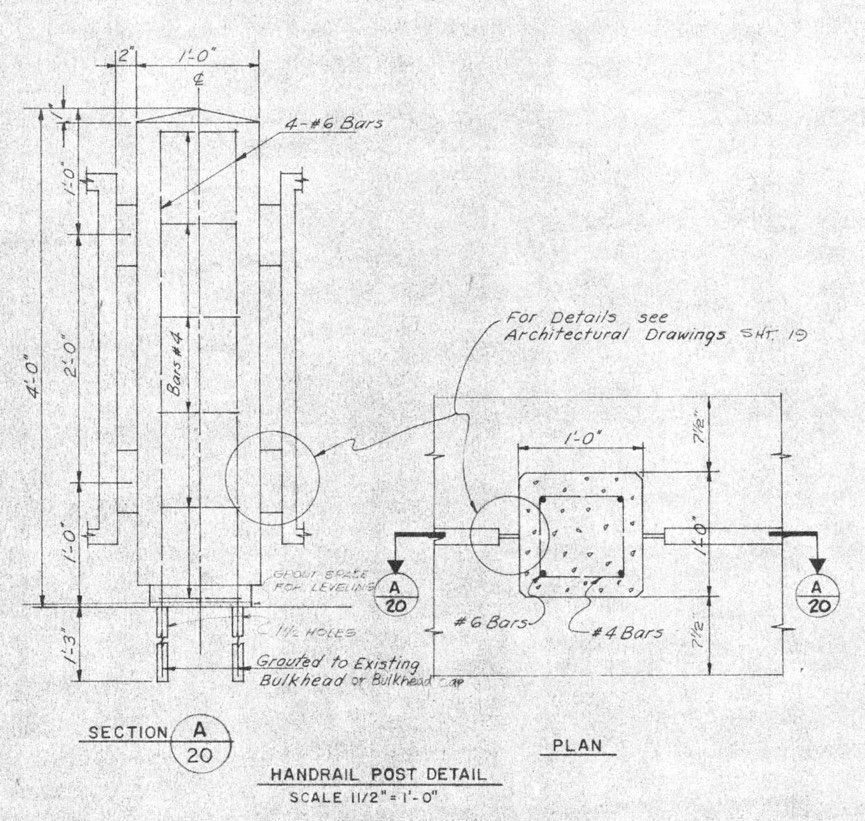

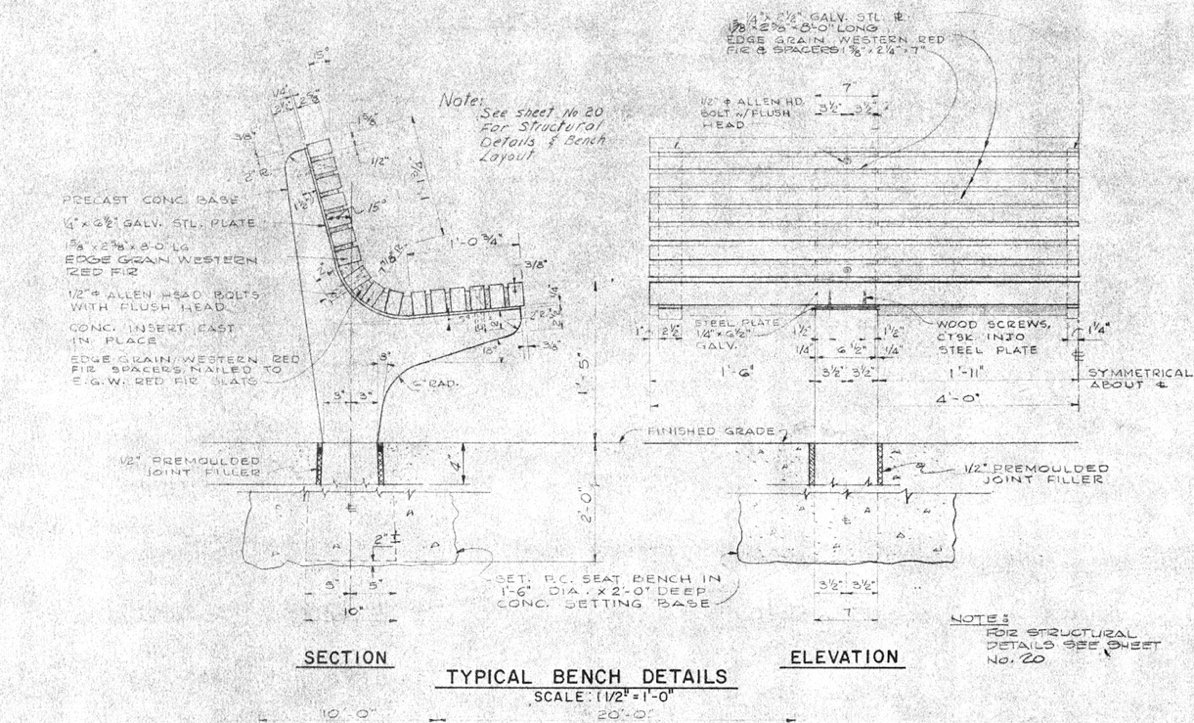

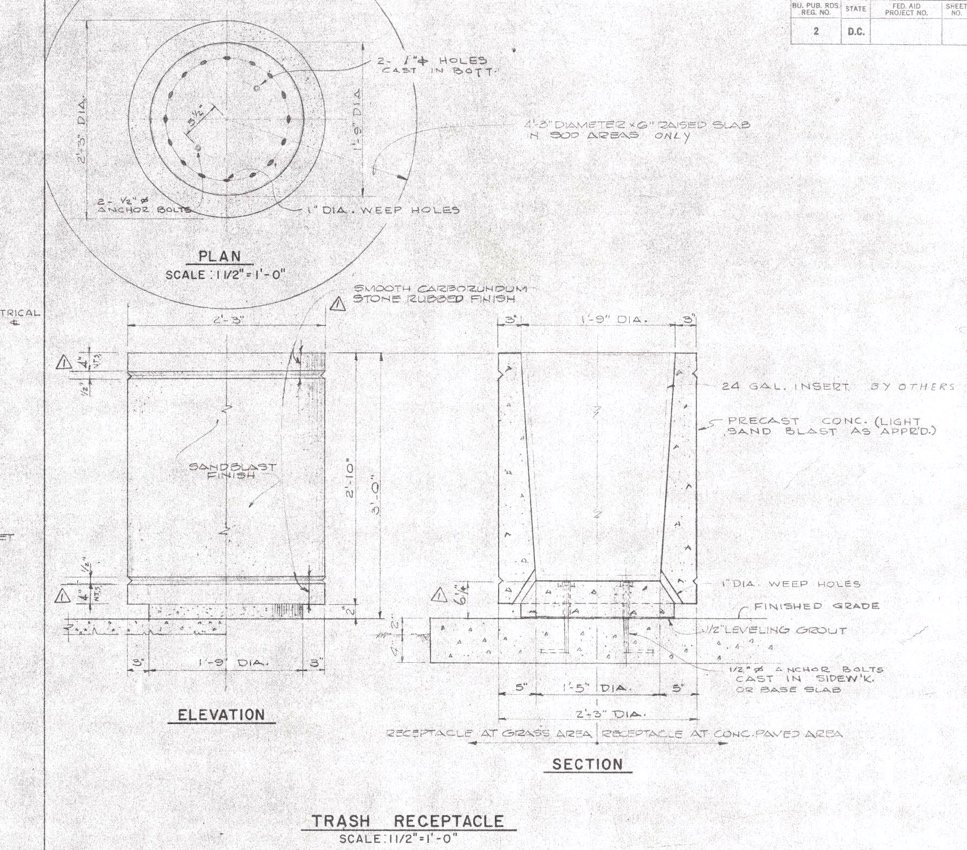

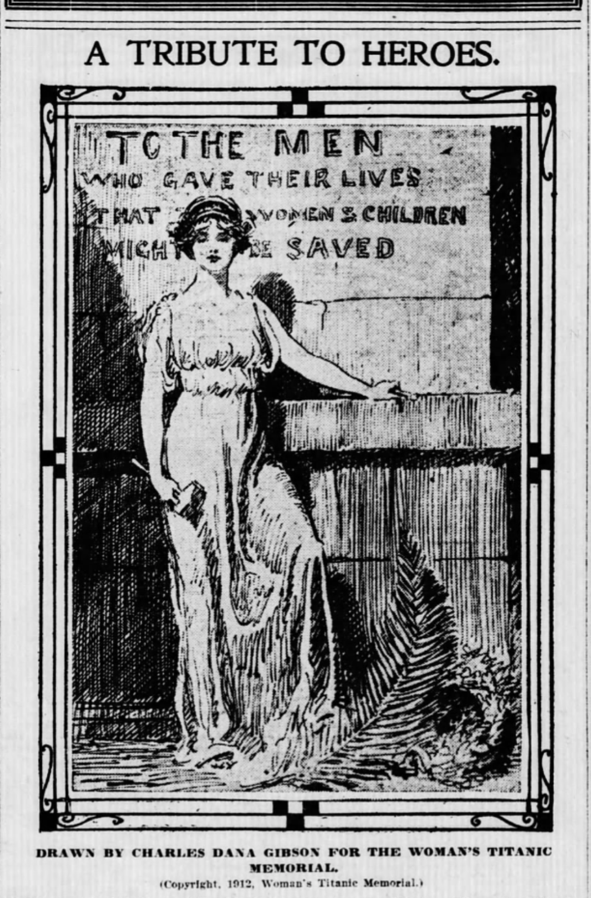

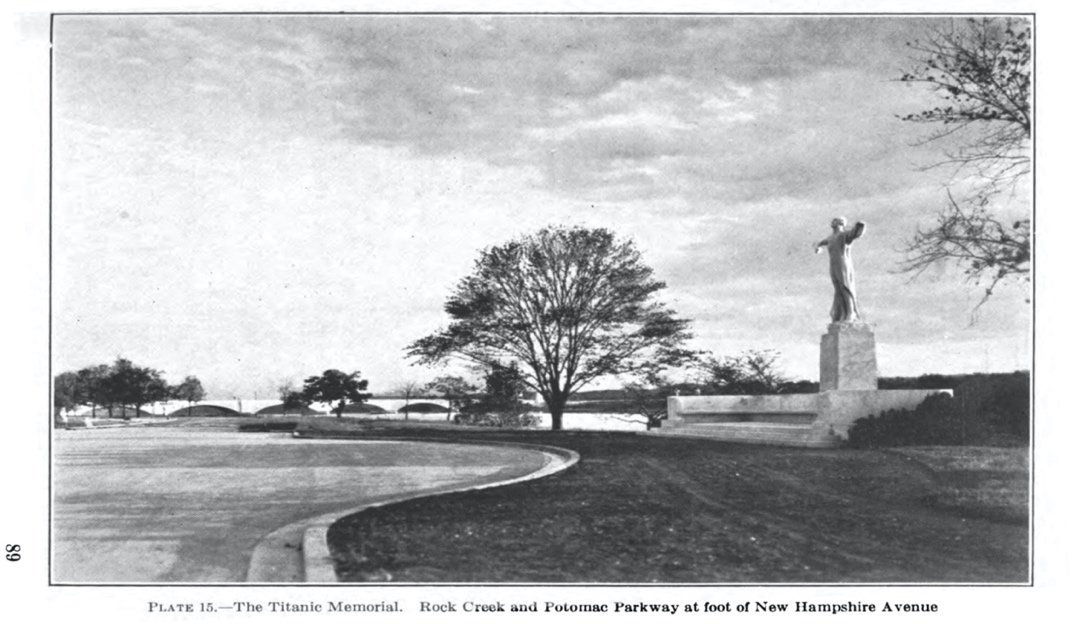

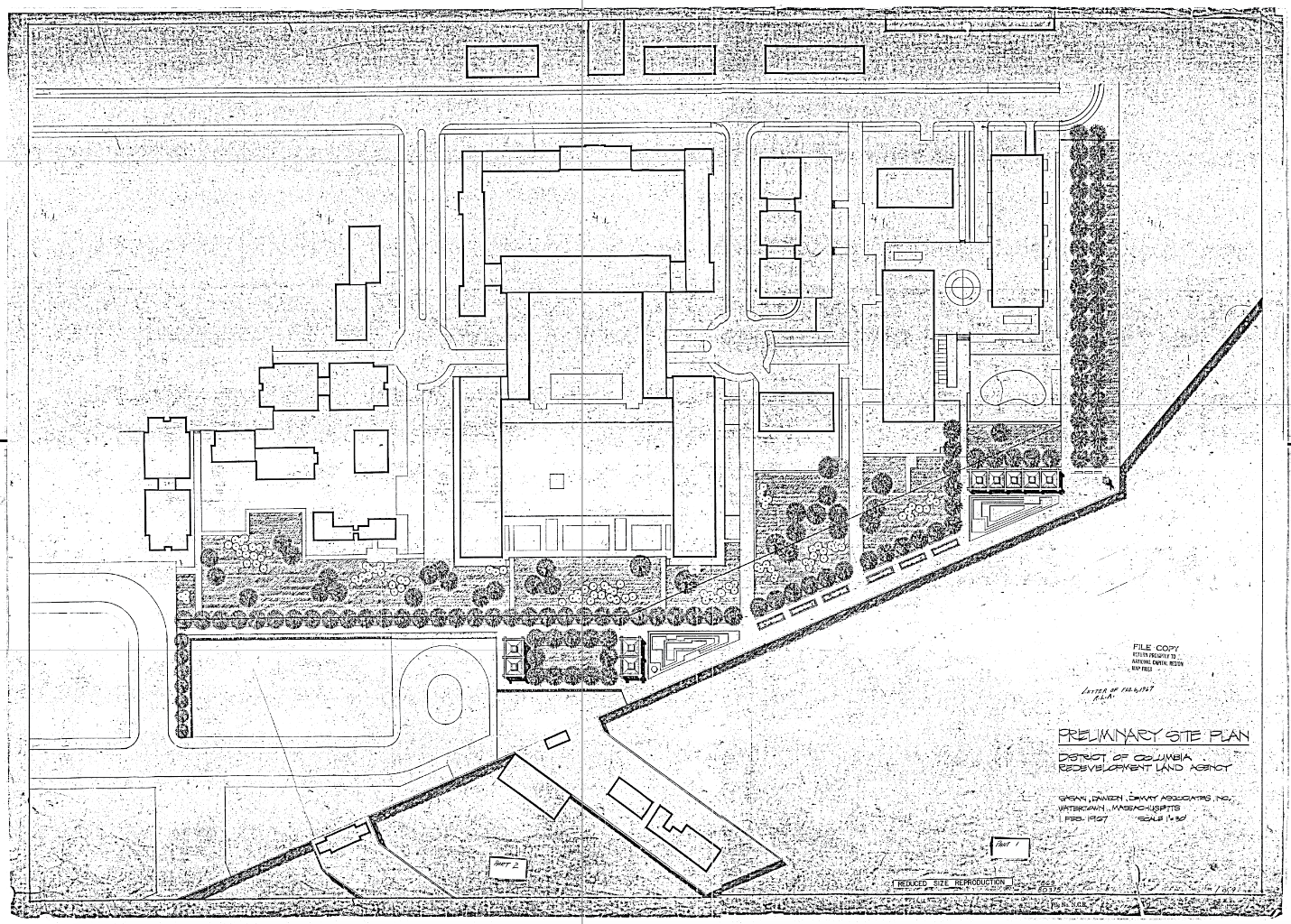

Sometime between 1965 and 1967, the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) selected landscape architecture firm Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay to develop the initial design for the study area (CFA Minutes April 19, 1967: 2; Exhibit b2). Under the direction of the Redevelopment Land Authority, Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay designed the park to incorporate landscape features with streamlined profiles and a Modernist material palette (including vegetation, structures, and small-scale features). During the design process, the CFA mandated that the design include Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s Titanic Memorial sculpture, created in 1916, which had been displaced from its former site along the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway. In 1967, the CFA approved the park design for the Titanic Memorial cultural landscape, and construction began in the following months.

Few changes have been made to the overall landscape of the Titanic Memorial park cultural landscape since the 1967-1968 design by Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay. The as-built 1968 design, including its spatial organization, land use, topography, circulation features, buildings and structures, views and vistas, and small-scale features, remains extant and legible in the park today.

SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY

The Titanic Memorial park cultural landscape derives local significance as a park designed and planned under the District of Columbia’s Southwest urban renewal program in the mid-20th century.

The cultural landscape is named for the Titanic Memorial sculpture located at the southwest corner of the cultural landscape. The sculpture was previously listed in the National Register of Historic Places on October 12, 2007. The period of significance for the Titanic Memorial sculpture is 1916-1930, a span that begins with the completion of the sculpture in 1916 and extends through 1930, when the sculpture and its base were installed at its former location along the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway. The Titanic Memorial sculpture is listed under Criterion C for its national significance in the area of Art, as part of the collection of commemorative sculptures located in Washington, DC. The Titanic Memorial sculpture is listed with Criteria Consideration B, as it was moved from its former location along the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway to the southwest waterfront in 1968.

This CLI concurs with the findings of the National Register designation for the Titanic Memorial sculpture’s national significance under Criterion C (with Criteria Consideration B), but recommends expanding the period of significance for the Titanic Memorial sculpture to 1914-1931, with national significance under Criterion Cand considers the sculpture’s National Register period of significance (1916-1930) to be a secondary period of significance for the full Titanic Memorial cultural landscape. This expanded period of significance begins when Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney won the commission to design the Titanic Memorial sculpture in 1914, and extends to 1931, when the sculpture was dedicated and opened to the public at its former site along the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway.

For the purposes of this CLI and the Titanic Memorial cultural landscape, this CLI recommends additional eligibility or consideration for inclusion on the National Register under the following criteria:

1967-1968, with local significance under Criterion A, based on the Titanic Memorial cultural landscape’s local significance as a park designed and planned under the District of Columbia’s Southwest urban renewal program in the mid-20th century;

1967-1968, with local significance under Criterion C, based on the cultural landscape’s 1967 design as a Modernist waterfront park envisioned by famed landscape architecture firm Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay.

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION SUMMARY AND CONDITION

This CLI finds that the Titanic Memorial park cultural landscape retains integrity based on the extant conditions that are consistent with its primary period of significance (1967-1968). Original landscape characteristics and features from the primary period of significance remain in place at Titanic Memorial park, including its use as a passive and active park, flat topography, L-shaped spatial composition, views of adjacent historic landmarks, Modernist planting scheme, location of the Titanic Memorial sculpture, concrete play areas, and small-scale features (including benches, lighting, and trash cans). The landscape displays all seven aspects of integrity, as defined by the National Register of Historic Places.

Map of site boundaries for the Titanic Memorial Park cultural landscape. (Graphic by CLI author, 2020)

[The Titanic Memorial Park CLI was written by Jacob Torkelson under the supervision of Molly Lester as part of the Urban Heritage Project, an initiative of PennPraxis and the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. It was completed between 2019-2020 under a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Area, National Park Service]

Full Text Available: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2288095