foodways: fort union

Fort Union National Monument, National Park Service, Watrous, NM

Aerial photograph of Fort Union National Monument in Watrous, New Mexico showing the fort layout and circulation patterns. (Arrott Collection, New Mexico Highlands University Special Collections, 1931).

Tasting Heritage: The Culinary Landscapes of Fort Union National Monument

A cultural landscape study of Fort Union National Monument through the lens of food.

Fort Union, a large, uniquely located economic hub, shaped, determined, and defined what was consumed, traded, and provided not only for the members of the fort but also for the region as a whole. Decisions made by the fort about what to eat, how much to eat, who ate what, and who could access and distribute food defined the social and cultural dynamics of the region. At the same time, individuals including New Mexicans challenged the established system, working alongside it to provide additional foodstuffs to the fort. Previous research has examined the role local communities held in supporting Fort Union, yet their narrative is inaccessible and hardly peopled; more often than not narratives about food at the fort focus on the military. In a similar way, detailed records of inventory and consumption exist in the military accounts, but little of the research examines how it was prepared, eaten, or where each of the ingredients came from.

This research builds upon previous studies by mapping the distribution of food through recipes and by peopling the social history of the Fort by constructing social narratives of individuals that dealt in food. Finally, this research proposes interpretive strategies using food as a tool to engage diverse audiences.

Introduction

In 1893, Lydia Spencer Lane affectionately reminisced on her time at Fort Union as an officer’s wife: “How I remember the sights, sounds, and odors…” she wrote in her autobiography I Married a Soldier. “And the smells! The smoke from the fires of cedar wood would have been sweet as a perfume if it had reached us in purity; but mixed with heavy odors from sheep and goat corrals, it was indescribable. I never get a whiff of burning cedar, even now, that the whole panorama does not rise up before me, and it is with a thrill of pleasure I recall the past, scents and all.”[i] Lane’s account was among several published at the turn of the century that depicted western life to “civilized” eastern society. During her time in the West, Lane crossed the Great Plains seven times by wagon train moving with her husband for various military assignments, including a posting at Fort Union. Much of what is understood about the fort, its peoples, their lives, and habits—particularly culinary ones—are discerned through first-person accounts like Lane’s. These limited glimpses into the lives at Fort Union depict a robust culinary landscape: foodstuffs being exchanged across the region from fort to fort; local Hispanos selling fresh produce, grains, and meats; officer’s wives striving to live eastern lives within limited western means; and soldiers simply trying to survive on military rations. Each of these tales humanizes—or peoples— the narratives of Fort Union and underlines the effect the fort had on transforming lifestyles and foodways in the West.

Fort Union, a large, uniquely located economic hub, shaped, determined, and defined what was consumed, traded, and provided not only for the members of the fort but also for the region as a whole. Decisions made by the fort about what to eat, how much to eat, who ate what, and who could access and distribute food defined the social and cultural dynamics of the region. At the same time, individuals including New Mexicans challenged the established system, working alongside it to provide additional foodstuffs to the fort. These individuals augmented the culinary landscape of the region by providing milk, grain, fruit, vegetables, and other commodities that the military economy of the fort failed to provide. Previous research has examined the role local communities held in supporting Fort Union, yet their narrative is inaccessible and hardly peopled; more often than not narratives about food at the fort focus on the military. In a similar way, detailed records of inventory and consumption exist in the military accounts, but little of the research examines how it was prepared, eaten, or where each of the ingredients came from.

The culinary landscape represents a significant, missing interpretive link and presents a unique opportunity that is ripe for study, a subject that all visitors can connect with: food. This research will build upon previous studies by peopling the social history already begun by scholars. Food as interpretation challenges traditional National Park Service sign-board and ranger-led tours by engaging visitors in kinesthetic and sensory ways. This research will examine the culinary landscape of Fort Union by constructing a social narrative of the cooks, servants, traders, wives, and other individuals that dealt in food to better understand and interpret the regional narrative of Fort Union. Archival evidence—particularly journals and other first-person accounts, like Lydia Spencer Lane’s—will be used to validate and personify the culinary narrative of the Fort.[ii] Additional analysis will utilize maps to examine how culinary features in the landscape may have been connected. Finally, this research will propose an interpretive strategy using food as a tool to engage diverse audiences at Fort Union.

Literature Review // Methodology

The literature on the culinary landscape and foodways at Fort Union ranges broadly across a multitude of topics. Military literature focuses on the transportation of goods across the country and the rations provided to soldiers, while seldom discussing the role civilians and locals held in supporting the fort. Social and ethnographic studies have done an excellent job at balancing out the military narrative by exploring the relationship of the fort to New Mexican communities and to the civilians living within and outside its walls. However, most of the literature regarding food is lacking in its “peopling” of the narrative. Put more simply, most of the stories of the cooks, commissary clerks, traders, farmers, bakers—what was eaten and by whom, and what was made or grown and who supplied it—are largely absent.

Military Role as Supply Depot/Distributor of Food

Fort Union held the role of Territory quartermaster depot from 1851-1879, providing food, clothing, shelter, and transportation for the army.[iii] While predominantly consisting of enlisted men, the military operation also employed a number of civilian workers who supplied and sold goods at the fort, a fact which Oliva argues has been overlooked until more recently in the scholarship of the Fort.[iv]

Social History

Few studies have examined what it was like to acquire, cook, and consume food at the Fort throughout its history. Oliva examines the first-person accounts of Bowen family members, among others, through their journals and he brings some much-needed life into the narrative. Using the journals of the Bowens, Oliva describes what it was like to eat at the fort. The journals suggest a high cost of living, the existence of largely processed goods provided by the fort, and the failed attempts by the military to cultivate the land.[v] Accounts like those of the Bowens also lay out some of the arrangements made with local communities to provide goods and produce not offered by the military. While the accounts of the Bowens provide invaluable insight into living and eating at the fort, they do not provide an understanding of who the food workers were. Likewise, little is said about how the food was made, or even the provenance of the various ingredients used in each meal; a study of this subject is ripe for investigation. Nothing is said about New Mexicans and their dietary habits, only that they traded goods with the fort. In the interest of promoting a more honest and diverse picture of the culinary landscape, more investigation is needed here.

However, the ethnographic study does an excellent job of discussing the role of New Mexicans in shaping the culinary landscape of the fort.[vi] The authors of the report make clear the relationship the fort had with the surrounding communities but falls short in discussing how culinary methods, food preparation, or recipes of the fort were changed and transformed by local communities and their resources or vice versa. The exchange of foodstuffs was much more than a direct exchange; it substantially altered the ways in which groups ate based on the availability of resources and the modifying factors of their environments.

Physical Fabric, Remnants at the Fort

In regard to physical fabric, Oliva details the goods provided at the fort but writes little about how each of the spaces was used. Oliva examines the store of the post sutler, the bakery, the commissary, a few kitchens, and the attempted farm and garden.[vii] However, more research is needed into how the spaces operated and how each of them connected to one another. The Historic Structure Report is the best account of sutler and traders row and warrants further investigation.[viii] Oliva also thoroughly investigated the attempts made by officials at Fort Union to create a garden near the fort as well as a substantial farm twenty miles north of the fort in Ocate.[ix] The Historic Structure Report notes many of the ways in which families or individuals subverted the traditional ration economy by raising their own crops and livestock.[x] The agricultural landscape is thoroughly described by Oliva and others, but its interpretation at the fort today could be improved and tied to the physical material fabric of the fort. Where are the trails or roads that connected each of these specialized food places? How do they relate? Where are the kitchens located—in the officers’ quarters, in the company barracks? Where is food stored—in cellars in some cases, in warehouses, in private homes? These questions have yet to be explored. The goal of this line of investigation is to identify specific “places” for interpretation within the culinary landscape of the fort.

Each of the main narratives, military, social, and material offer varying approaches to understanding the culinary landscape and can connect and contrast across lines to offer a dynamic range of interpretations for Fort Union.

Research Design and Methods

This research is divided into five parts:

1. The creation of a ‘cookbook’ or ‘recipe guide’ that includes two period recipes. This cookbook tracks the provenance of each of the ingredients used and includes a map of where they came from. This recipe analysis will serve as an interpretive tool to help visitors understand the larger culinary landscape and engage with it on a more personal level: food.

a. Method: Primary sources—largely letters of officer’s wives— were used to uncover historic recipes. Provenance was determined using these letters and other documents from the fort. Deciding which ingredients were provided by the military, and which were not was key in understanding the dominant and augmented culinary landscape. Where possible each recipe determines where ingredients were shipped from or manufactured from. For those ingredients not provided by the military, journals and other primary sources—like those of the Bowens—were used to decide where would they likely have come from.

2. Using military records and biographical research where possible, short social biographies or ‘trading card’ type bios of key food staff including Hispanos, cooks, servants, and wives were created. These follow the recipes in this paper to people the narrative.

a. Method: Due to the temporary and highly changeful nature of foodways, the identities of many of the individuals who worked with food remain unknown. A few glimpses are offered through letters and census data. These were used to begin to shed light on their narratives.

3. Preliminary large-scale mapping was created and added as an appendix to the “cookbook”, locating major sources, both locally and nationally of food provenance. It will consider the sources of food and the locations of food processing, largely focusing on the movement of goods from their sources to final consumption.

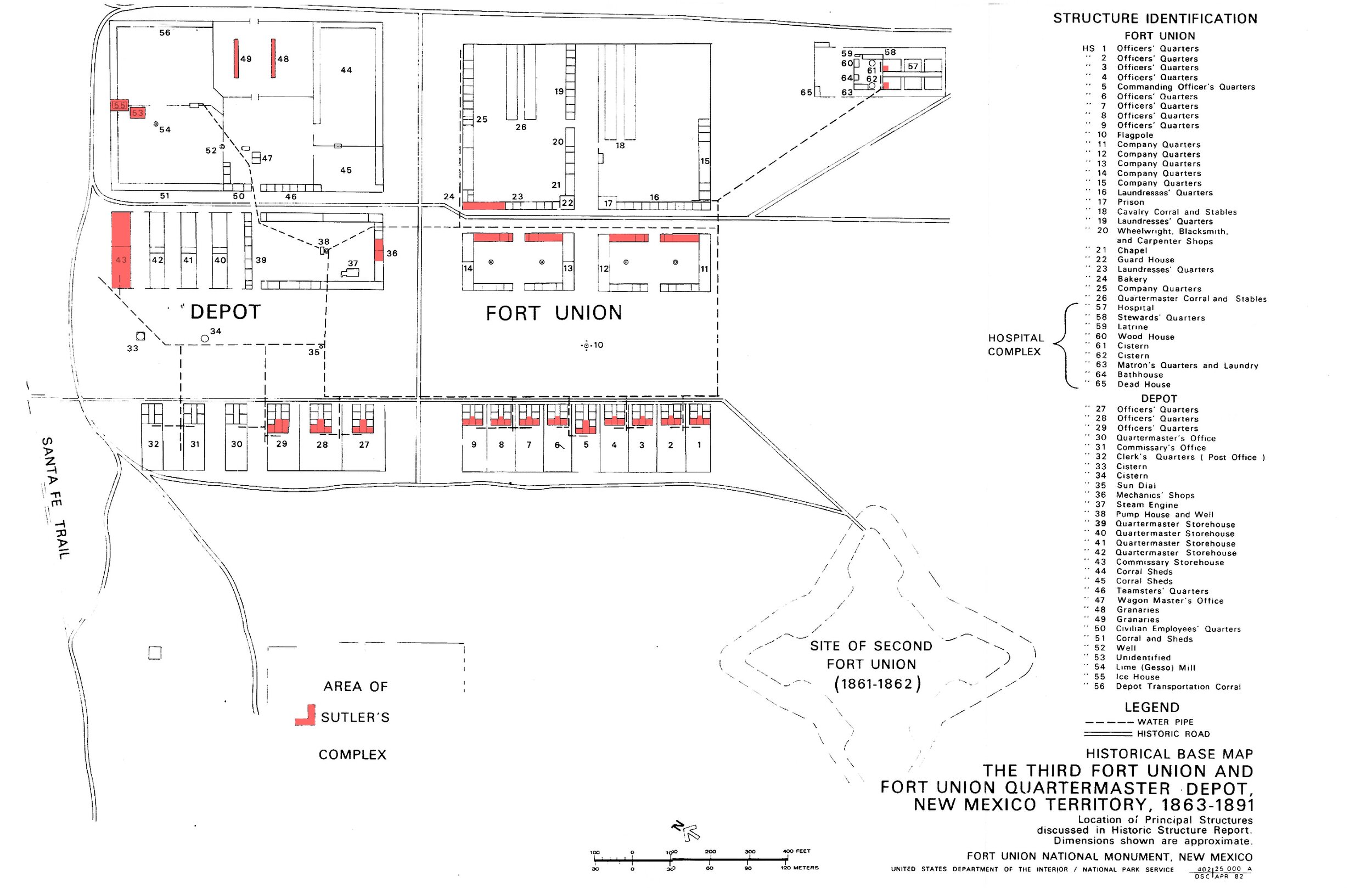

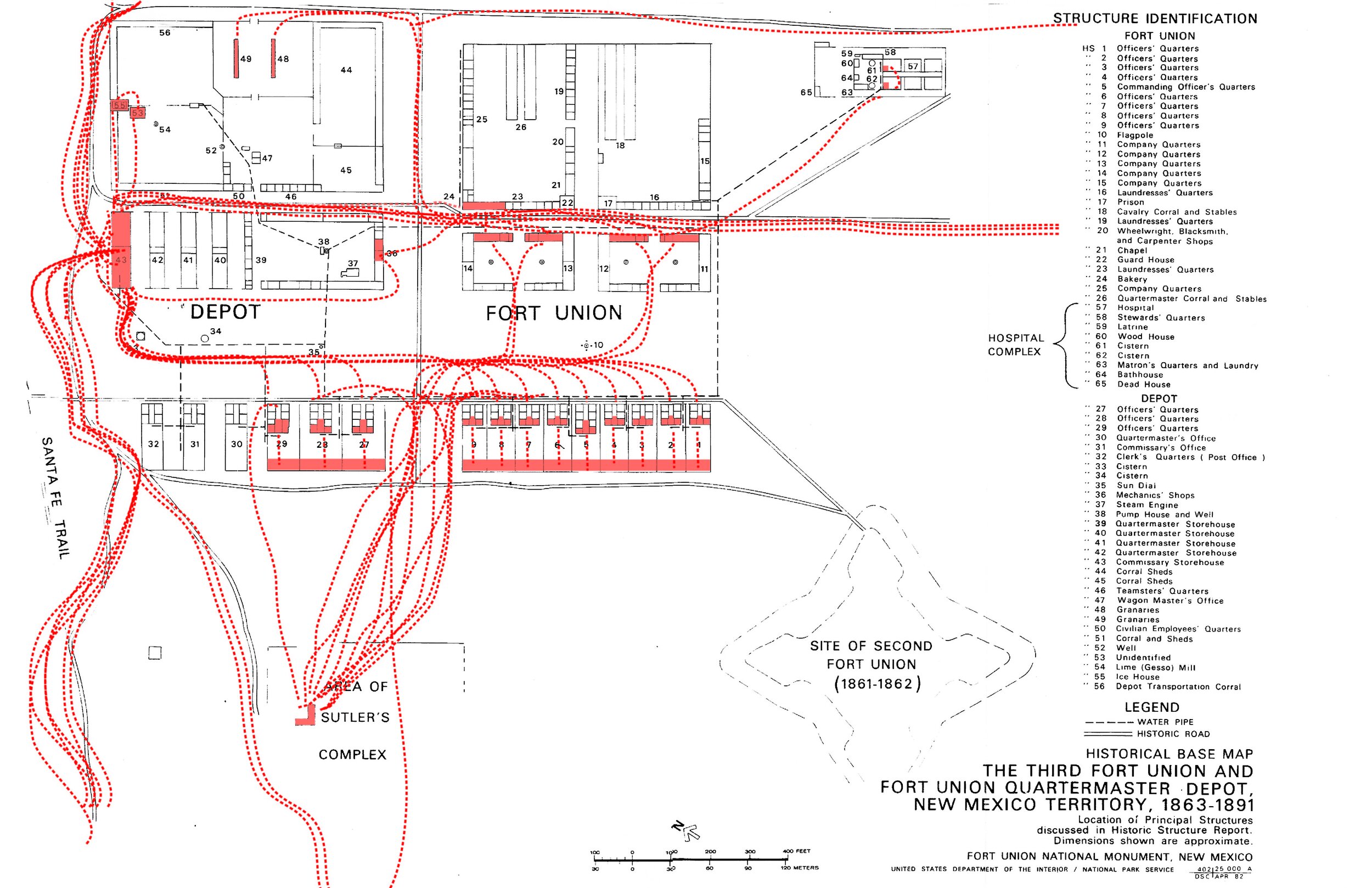

4. Likewise, a zoomed-out plan of fort union begins to surmise how food “hubs” within the fort were connected. Based on satellite photos, and inferencing, it depicts possible social trails that show how food production and storage facilities might have been connected. At the very least a map locates each of the food facilities.

a. Method: These maps were created in Illustrator using overlays of U.S. and regional maps, as well as the plan of Fort.

5. Lastly, a section of this paper addresses how food or the culinary landscape could be interpreted at the site. This consists of several paragraphs regarding interpretive activities like cooking and suggestions for new locations for interpretive. New interpretation allows the site to be seen as a catalyst in change the regional economic and food systems.

Mapping Foodways: Where did food at the Fort come from?

National Contexts:

Fort Union held the role of Territory quartermaster depot from 1851-1879, providing food, clothing, shelter, and transportation for the army. While predominantly consisting of enlisted men, the military operation also employed a number of civilian workers who supplied and sold goods at the fort, a fact which Oliva argues has been overlooked until more recently in the scholarship of the Fort. Two to three thousand wagons of freight were unloaded at the commissary each year.[xi] Modern signboards compare these large wagon trains to the mass-freight system of semi-trucks used today. The goods the wagons deposited in the commissary at Fort Union were used to supply all of the forts and camps of the southwest; in every way, Fort Union was the driver of the southwestern economy for much of the second half of the 19th-century.

Processed, mass-produced, and manufactured goods were shipped from the East and in some cases as far away as Europe. Hardtack, salted meat and fish, coffee, tea, sugar, salt, vinegar, hominy, cornmeal, onions, potatoes, canned goods, bottled foods, flour all arrived at Fort Union by wagon for dissemination to regional posts. Goods from the fort reach posts in Oklahoma, Mexico, Colorado, Texas, Arizona, California, and New Mexico (Fig, 1). Between 1860 and 1867 there were well over one thousand civilians employed by the fort, most of which were involved in the transportation of goods across the vast network of military encampment in the southwest. In the 1870 census, there were one-hundred civilian employees working at Fort Union. Roughly forty of these one hundred civilians were teamsters that transported these goods to distant forts, the majority of which were Hispanos.[xii]

Figure 1. Map depicting the sphere of influence of Fort Union. Foodstuffs and other goods for the entire region were funneled through Fort Union and then disseminated to the entire region of the southwest. (FOUN, NPS; Annotated by author)

Compounding this absence further was the deployment of the majority of garrisoned units on Indian campaigns. Mrs. Orsemus Boyd, the wife of a Fort Union quartermaster, recalled this loneliness. “We were always delighted to welcome back the troops from their Indian reconnoitering,” she wrote. “Life was so dull without them. During their absence, the garrison would consist perhaps of only one company of infantry, with its captain and lieutenant.”[xiii] Boyd’s recollections highlight the backcountry v. basecamp reality of Fort Union. The majority of resources of the Fort at any given time —particularly processed and canned foods—were in the field with teamsters and soldiers conducting the business of the fort.

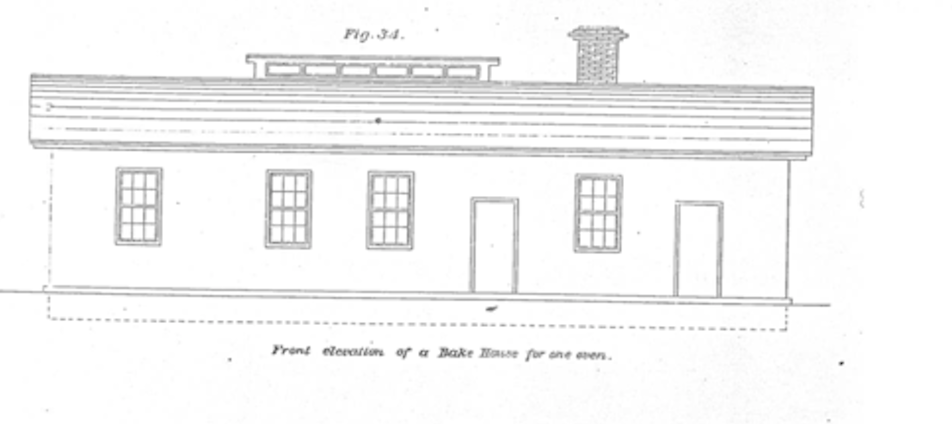

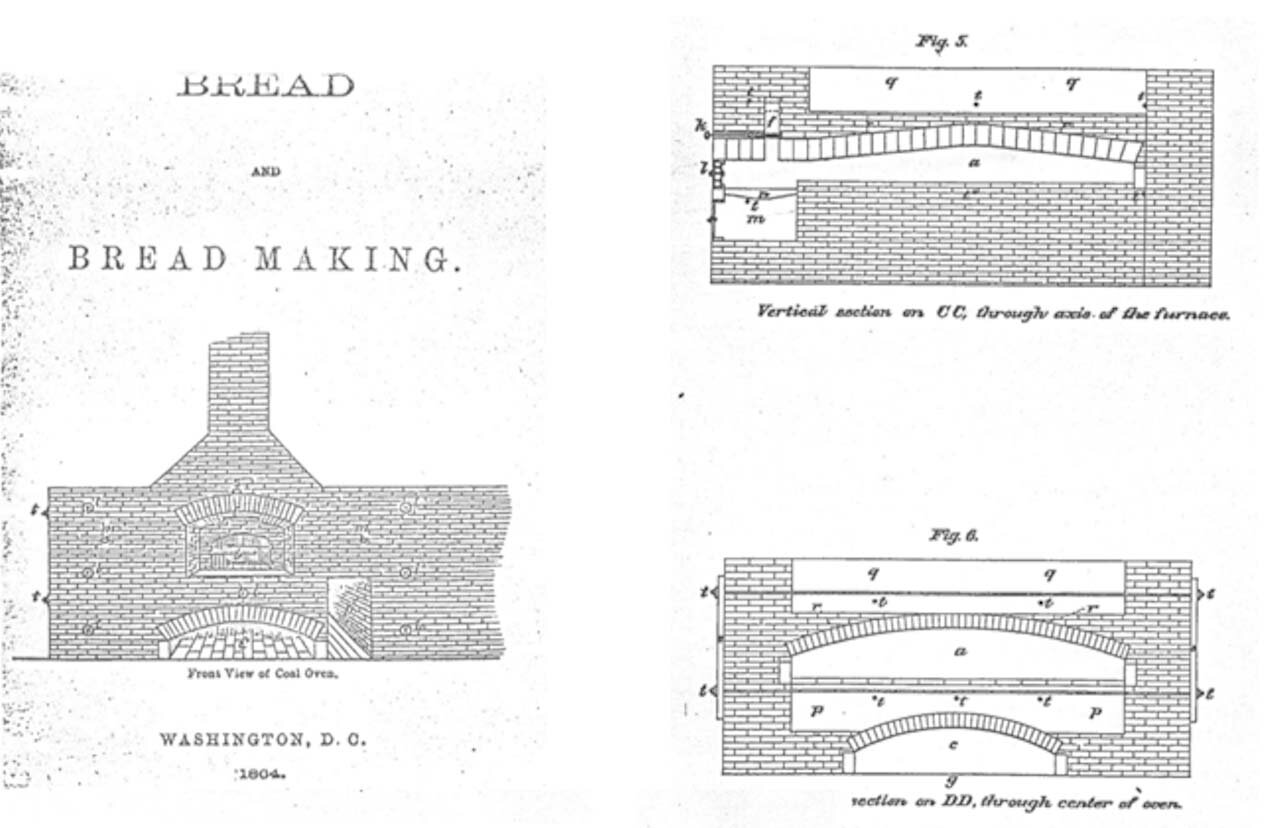

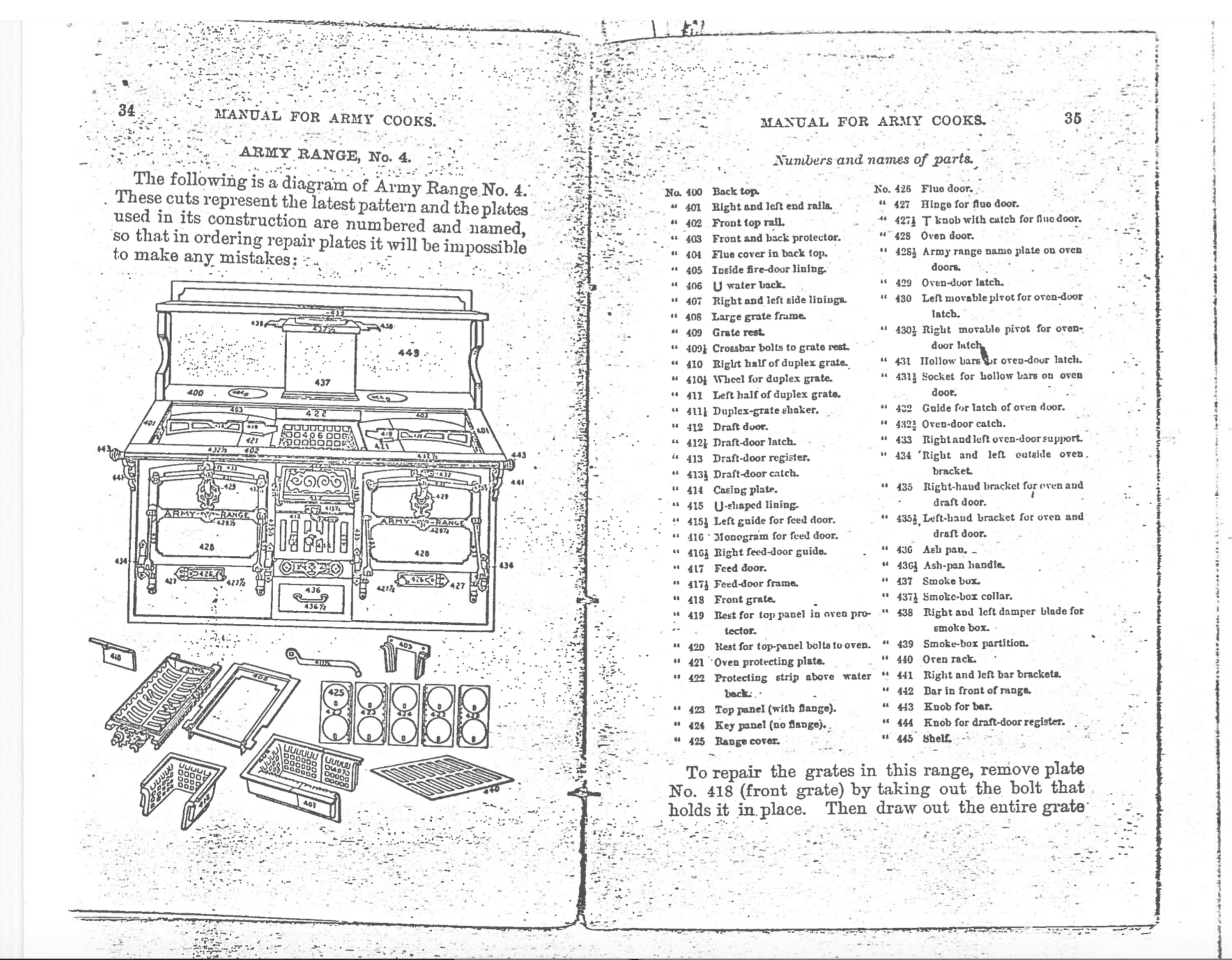

Nonetheless, life for soldiers on campaigns was not nearly as joyous or food-filled as during their homecoming. Food was scarce and what was provided was often inedible. Unique cooking implements were created by the military for field kitchens to bake bread and to make other fresh foods (Fig. 2). However, these implements were heavy, cumbersome, and labor-intensive to install.[xiv] No accounts by soldiers indicate the existence of such implements at Fort Union; more likely than not, these implements were never meant for western campaigns and would never have reached Fort Union, certainly not by wagon train. These large iron contraptions rather represented the ideal that the Army Manual for Cooks, and the heads of the military in the east, strived for.

Figure 2. Schematic depicting a cast-iron field oven for use by traveling troops. The oven’s weight and labor-intensive set up likely prohibited it from taking hold in Western campaigns. (Manual for Army Cooks 1883 in FOUN Archives)

Second Lieutenant A.R. King in a letter to Brevet Colonel T. F. Chalfin more accurately described the culinary circumstances of the troops. In his letter King describes a rancid ration of cod-fish given to the troops under his command:

Sir,

I have the honor to respectfully submit the following for action. The “cod-fish” issued by the commissary in the department, is considered by myself and the officers and men of this command to be to totally unfit for use, for the following reasons:

1st The fish is rancid and old.

2nd The recent issue of rations by the government, do not afford any facilities by which said “fish” may be properly cooked; and the men are consequently compelled to buy proper ingredients to make it fit for use.

3rd Men are going on detached service from their troops are compelled to take their rations, in part at least, in the substitute for bacon; and on the march, there is very little if any opportunity to cook such food. I would therefore respectfully request the use of this ration be replaced by something that will afford better facilities for properly cooking.

A. R. King

2nd Lieut. 3d US Cavy

Commanding Troop “I”[xv]

Thinking broadly, one can only imagine which part of the east coast the “cod-fish” would have come from. It certainly would not have come from the land-locked area of New Mexico. However, what is clear, is that the ration of cod-fish was shipped across the country via wagon train to Fort Union for somewhere out east. Here, troop rations at Fort Union connect to much larger national foodways and a national economy. Perhaps what is most interesting is how the troops worked around this rigid system to barter for goods to make the fish more palatable or even to replace it with other substitutes like bacon. In any case, the case of the cod-fish makes clear the national dimension of Fort Union’s foodways.

Fort-wide Contexts:

Zooming in from the macro-level to a fort-wide level creates an entirely new set of questions about food: Where did goods move throughout the fort? Was there a difference in what each person at the fort ate? Where were goods stored at the fort? Questions like this frame the culinary landscapes of the fort into a new discussion of rank, gender, and race (Fig. 3, 4). These maps highlight all of the sites at the fort involved in the production, distribution, storage, or consumption of food. This map was made by inferencing connections between food sites using satellite images of existing “ghost paths” and written historical documents. Diagrams like this one only begin to hint at how these complex spaces were linked through foodways. More study is needed to establish foodways more concretely.

This map reveals a clear hierarchy of foodways among officers, enlisted men, and civilians. Among commissioned officers, wives were able to trade amongst themselves for goods. Officers built gardens, chicken coops, stables, corrals, cellars, and servant quarters all designed to attend to their culinary needs. This is reflected in the relative area of red spaces in the officers’ quarters as compared to those of the enlisted. Regular soldiers did not have as much agency. Most resorted to visiting the post sutler’s store or trading among themselves. A daily ration of a soldier included:

Fixed Daily Allowance for one person:

12 ounces of pork or bacon or 1 pound, 4 ounces of salt or fresh beef

1 pound, 6 ounces soft bread or flour or 1 pound hard bread

4 ounces of cornmeal[xvi]

Unlike the officers’ readily available supply of produce, within the enlisted’s personal allowance there were no fruits or vegetables. Rather commodified rations, like fruits, vegetables, beans, and coffee were issued per one hundred rations. These were then split into shared dining facilities in the quarters of the enlisted men. To every one-hundred rations:

15 pounds of beans or peas

10 pounds of rice or hominy

10 pounds of green coffee, or 8 pounds roasted, or 1 pound, 8 ounces of tea

15 pounds of sugar

4 quarts of vinegar

1 pound, 4 ounces of adamantine or star candles

3 pounds of soap

3 pounds, 12 ounces of salt

4 ounces of pepper

30 ounces of potatoes, when practicable

1 quart of molasses[xvii]

With such a limited ration, it is easy to understand why soldiers often had scurvy at the fort. In the earlier years of the first fort, this was most common. The surgeon at the time recommended a special ration be issued to the troops consisting of chopped cabbage, beats, or boiled turnips soaked in vinegar, all of which “can be had in the country round or can be obtained from Fort Sumner.”[xviii]

Agriculture at the Fort

As Fort Union grew in the years of the third fort, so did the local economy surrounding the fort. Increasingly, the fort relied on New Mexicans to provide goods like fruits, grains, and vegetables which they could not provide to their troops. Since little exists in the written record about the New Mexican presence we can only infer how and where they transported goods through the fort. However, what is clear is the role they played in supporting the fort after the military failed to cultivate crops in the arid climate. Without the New Mexican’s agricultural prowess, the whole endeavor of Fort Union would have succumbed to starvation, or disease long before its decline in the 1890s. In 1851, Fort Union leased a large plot of land from Manuel Alvarez 23 miles to the north of the fort at Ocaté for the creation of a large farm.[xix] However, not long after, the farm failed. New Mexican’s familiarity with agricultural practices in the arid environment proved to not only an asset for the fort, but also for the economic development of their communities

Officer’s Self Sufficiency

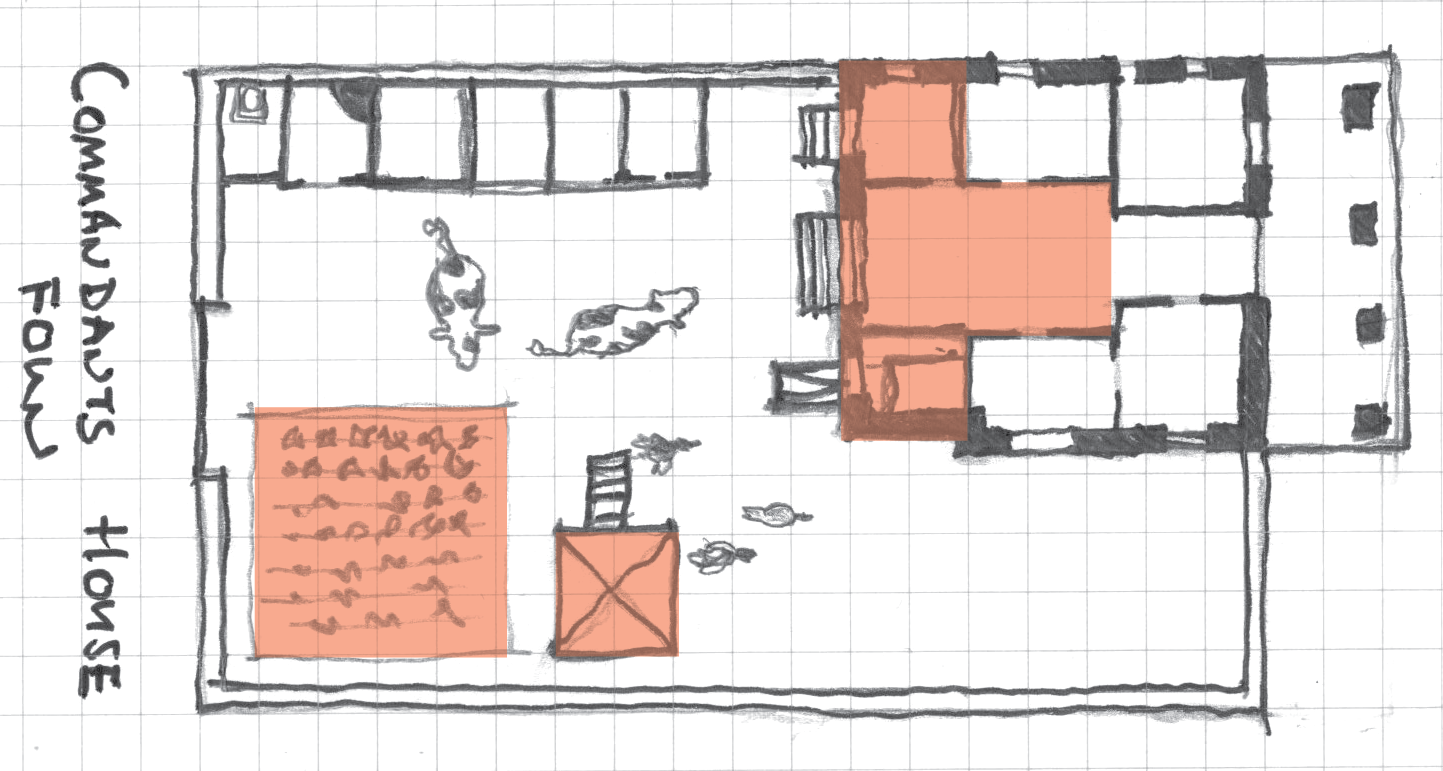

The officer’s and their families were perhaps the best off in terms of food diversity within the culinary landscape. In a letter to her mother, Katie Bowen highlights her own agency in preparing meals. She made her own butter, grew vegetables behind her house, and baked her own dishes (Fig. 5):

We have plenty of vegetables from the garden. We had peas the 21st of June and have since had beets, cabbage, turnips, salad and radishes. The Mexicans bring in onions and a wild currant that is very much like the black currant and makes nice pies and jelly. Eggs we have in any quantity and will have pullets enough to lay all winter. We have about eighty chickens. Many have been lost, but whether it was because they were born in the old of the moon or not I cannot say. We are soon to begin eating some of the big roosters, for corn is not to be bought till the new crop comes in. Everything goes on well, only sometimes. … This month we are going to kill our calf and then I shall put down butter for winter. We make more than we use now, but I give it to my neighbors who are less fortunate. I am going to make up a lot of fruit cake this week. Tomorrow I am going to have mincemeat for pies put down and before Saturday night have two loaves of Christmas cake baked which will last all winter. Isaac carried fried sausages, doughnuts and butter to last him to his journeys end and back. Our hens give us plenty of eggs and we feed them red pepper on their food to keep them laying. The Mexicans know the secret.[xx]

Bowen benefited from the local trade network but also created her own by trading eggs and butter among the other households. What often worried officer’s wives, was not necessarily the ingredients they had at their disposal, but how they could prepare them in a civilized way. Lydia Spencer Boyd lamented on this fact when she wrote, “You will see, from the forgoing, house-keeping on the frontier has its drawbacks. We have plenty to eat, such as it was, but we thought it not always dainty enough to set before our visitors.”[xxi]

Figure 5. Sketch of post commander’s house. Highlighted in red are the garden, chicken coop, kitchen, cellar, and dining room. (Sketch by Jake Torkelson, 2018)

The High Cost of Living and New Mexicans

Nonetheless, what worried officer’s wives the most, was the high cost of living associated with keeping a reputable household in the West. In a letter to her mother, Bowen recalls that American flour cost $11.78 per 100 pounds, while New Mexican flour was 7 7.8 cents cheaper per pound. Lamenting on this reality, Bowen wrote, “It is rather tough for with what we pay for the commonest things here would buy us luxuries in the States and at present we are only allowed to buy one ration for every member of our family which leaves us nothing for hospitality.”[xxii] Wives increasingly found themselves turning to “Mexican” alternatives to fulfill their needs. The rates were cheaper but necessitated a shift in diet. Mexican four, made from corn, was not the same wheat flour officer’s wives were used to eating in the east. New Mexicans altered the culinary landscapes of the inhabitants at Fort Union by providing alternatives to American goods at low-costs.

Tracking Recipes: Where do ingredients come from?

Recipes are among the most ubiquitous items in any household. Yet, each recipe is different. Each family, culture, place adapts the recipe based on their own needs and resources. By analyzing recipes, it is much easier to understand the foodways in their many scales. Locating where each ingredient came from can offer great insight into how the culinary landscape of Fort Union operated. Cookbooks were not common in the early years of the fort; rather, only a few were widely circulated. Perhaps the most prolific and widely used was The Virginia Housewife by Mary Randolph. Charlotte Sibley, wife of an early post commander recalls using the books in her memoir. Despite the book’s popularity many of the recipes did not adapt well to the altitude of western life. Sibley expressed the need a make a new cookbook adapted to New Mexican housekeepers.[xxiii] The only recipe explicitly delineated by former occupants of Fort Union was written down by Katie Bowen for a breakfast cake:

A Mule power corn mill furnishes us with nice corn meal and in lieu of buckwheat cakes I will send you the recipe of our breakfast cake. 1 pint sifted meal; 1 pint sour or buttermilk sweetened with saleratus; 2 spoonfuls melted butter and two eggs. If you do not find this nice, if well bakes in an oven or hot skillet, then it must be owing to the climate. I pour the mixture into a skillet and put a bake oven cover on covered with hot coals and it always comes out like a loaf of sponge cake. The three pullets Col Alexander gave us lay as many eggs as we can use, but Isaac sent for a dozen hens and they will be here tomorrow.” [xxiv]

Breakfast Cake

1 pint sifted meal

1 pint sour or buttermilk sweetened with saleratus (baking soda)

2 spoonful’s melted butter

2 Eggs

Pour mixture into skillet. Bake in oven or hot skillet covered, coals on top.

The ingredients of this recipe can be broken down into three levels: national, regional, and household. Saleratus, an early form of baking powder and soda, was exclusively manufactured in the Northeast during and after the Civil War and represents the national scale of foodways in this recipe.[xxv] It would have come from as far away as New York City, where precursors to companies like the Arm and Hammer company were manufacturing and experimenting with cheaper American versions of baking soda in order to outcompete European alternatives.[xxvi] Bowen herself wrote of producing her own butter and eggs in her back yard, at the household scale. The sifted meal would have been purchased from New Mexican mills in the region. Bowen recalls getting flour and meal from mills near Mora, roughly thirty miles distant.

To Make Mincemeat for Pies

1 quart grated calves or hog’s feet

1 quart chopped apples

1 quart chopped currants and raisins

1 quart brown sugar

1 quart cider

1 pint brandy

1 teaspoon of mace, cloves, nutmeg, black pepper, and salt

1 quart flour

1 pound butter

To make the crust: quart of flour mixed with cold water until stiff, kneaded, rolled out. Add salt and 1 lb butter,

Boil either calves or hog’s feet till tender, grate. Take one quart of this, one [quart] of chopped apples, the same of currants, raisins, good brown sugar, and cider, with a pint of brandy; add a teaspoon of pounded mace, one of cloves, and of nutmegs; mix all of these together intimately. Pour into pie pan; add teaspoon of black pepper, one of salt, cover with pie crust, cover with citron sliced thin, and garnish it with crust cut in fanciful shapes.

In her letters to her mother, Bowen also mentions baking a mincemeat pie for the Christmas holiday. She writes:

The Mexicans bring in onions and a wild currant that is very much like the black currant and makes nice pies and jelly. Eggs we have in any quantity and will have pullets enough to lay all winter. We have about eighty chickens. … This month we are going to kill our calf and then I shall put down butter for winter. We make more than we use now, but I give it to my neighbors who are less fortunate. I am going to make up a lot of fruit cake this week. Tomorrow I am going to have mincemeat for pies put down and before Saturday night have two loaves of Christmas cake baked which will last all winter.”[xxvii]

From her household, Bowen would have gathered her own eggs, produced her own butter, and ground her own calf’s feet. In a previous letter, Bowen wrote of receiving apples in the male from the states. Currants, raisins, and flour likely would have come from New Mexicans. Most spices and especially the cider and brandy would have been imported from the East. In more ways than one, a recipe using this expansive network of resources would not have been commonly used. Here, the occasion is Christmas, and it would seem all stops were pulled out to make the mincemeat pied for the holiday.

Analyzing Physical Remains: Where was food produced, stored, and disseminated at the Fort?

Among the greatest challenges to the interpretation of the culinary landscape at Fort Union is the relative lack of physical remains. Where physical evidence of foodways does exist, the paths that visitors walk on do not bring them nearby. Food as interpretation has the potential to enliven the dead spaces of the fort, however, in order to do that paths must be changed and circulation in and around places of food must be increased.

The remains most obvious and ready for interpretation include the bakery, quartermaster, and post commander’s cellars, and the general prevalence of artifacts on the ground. These remains fall into three categories: food preparation as evidence of foodways, food storage as evidence of foodways, and artifacts as evidence of foodways.

Food Preparation as evidence of foodways: The Bakery

The Bakery, having been built solidly of brick, stone, and mortar is the most obvious and readily accessible location from which to interpret food. However, all that remains of the bakery building is the oven. The wooden or adobe superstructure that would have housed the raw ingredients and area of dough making is missing (Fig. 6). The brick arched oven where the bread was baked has since collapsed but can be seen in the rear of the oven (Fig. 7). Likewise, the chimney no longer exists. Flues at the front and back of the oven would have drawn heat evenly across the oven to create a controlled baking environment (Left; Fig. 7). While baking, bakers would have actively stoked a fire near the opening on the righthand side of the photo. The oven door was above the limestone at the center of the photo; here they would have inserted and extracted bread (Fig. 8).[xxviii]

Bread was a central component of a soldier’s daily ration at the fort. Much of this would have been baked en-masse at the post bakery. As such, the room adjacent to the oven was where the dough was mixed, kneaded, and shaped. Bread troughs were used to make large amounts of dough to meet the needs of the post. Flour and water were added to the trough, while several men with paddles walked through it kneading and mixing the dough. Each man would move from the front to the rear, crossing paths with the other, repeating until the dough was kneaded. In 1981, Roy Lyman of Watrous donated Fort Union bakery’s bread trough back to the collection of the park. While using the historical bread trough for interpretive cooking might not be an option, a replica in which visitors—particularly kids—could “mix” dough in a trough could certainly change the dynamic of the interpretation and has the potential to actively engage visitors.

It is, however, important to note that baking occurred on many scales at the fort. While the post bakery produced that vast majority of breads, each kitchen had its own oven. Indeed, many of these ovens still exist but are covered over with adobe encasement (Fig. 9). The ghost of a brick oven exists in the mechanic’s corral. Other such ovens likely exist behind adobe encasement in officers’ quarters and in the hospital. These would have been used for specific meal-based cooking, as opposed to large-scale fort wide meal preparation.

In a similar way, all of the kitchens, particularly those of the officer’s quarters, would have had cast iron stoves (Fig. 10). Most of the cooking would have been done on stoves, as opposed to fireplaces or ovens. The majority of the public is left to believe that food was cooked in fireplaces because this is all that remains. Brining back stoves or interpreting them in some way is essential to understanding how people ate and lived at the fort.

Food Storage as Evidence of Foodways

The highest-ranking officers, the post commander, and the quartermaster had the nicest most substantial homes. With these homes came all the conveniences of modern living, including substantial below-ground root cellars for cold storage (Fig. 11). Each cellar is directly below the kitchens and has its own exterior exit/entrance. The cellar at the quartermaster’s house has a built-in shelf, it is easy to surmise, for the storage of canned goods or other items best kept off the ground. The sturdier built post commander’s house cellar is much deeper. It also has sloped walls that could have facilitated the movement of goods in and out of the cellar.

These cellars, along with the large basement level of the commissary, are the only rooms that still exist whose purpose was strictly the storage of food. Ice was regularly harvested by the fort from the pounds a few miles south for use in the summer months to keep food cold and for use in the hospital.[xxix] The commander and quartermaster likely would have had their own ice harvested and stored in their cellars to keep their food from spoiling.

These are rare examples of food storage that should be included on a new pathway that brings visitors into the homes of the officers. Little physical evidence exists that discusses food storage, and nothing mentions the existence of a basement level at Fort Union.

Figure 11. : Photographs of the cellars at the post commander and quartermaster residences. Highlighted in red are the routes food entered and exited the residences. (Photo and annotations by author, 2018)

Artifacts as Evidence of Foodways

Park staff made it clear to students that the collection of on-site artifacts was no longer of interest to management. The fort has neither the staff nor exhibition space to display its vast collection of artifacts. In an ideal world, visitors should be allowed to explore the fort going off trails. As researchers, the space came alive when we were able to rummage through the grass and find evidence of life at the fort. When it comes to finding artifacts, the question becomes: What needs to be preserved? Can the public be allowed to roam to grounds, as researchers are?

A semi laissez-faire approach like this could benefit visitors immensely. While an unguided, free-for-all approach will never pass, guided off-path tours with park staff could wholly change the site’s interpretation. The spontaneity of stumbling upon a spoon (Fig. 12), rusty nail, oil crock (Fig. 13), or champagne bottle (Fig. 14) can create new understandings and lasting memories, while under the careful supervision of park staff. Stumbling upon artifacts, which tend to be almost exclusively food-related (e.g. china, bottles, cookware), allows visitors to connect with food in a new, place-based way.

Peopleing the Narrative: Who prepared, exchanged, and transported food?

Foodways and the culinary landscape are important narratives in any discussion of Fort Union. However, the topic would be nothing without the stories of people that were part of that history. Food comes alive when people are connected to it, just as a family recipe is often linked to a certain member. In this way, physical fabric and recipes come together with social history to create a diverse and dynamic narrative.

The Post Wives and their Servants

Lydia Spencer Lane

Quotes from Mrs. Lane have appeared through this paper, as she created one of the most vivid and lively accounts of life at Fort Union. Lane thrived in her environment. with the help of her servants. Nonetheless, it is easy to forget that most people at the fort did not live the glamorous and privileged life that she did. Post wives were expected to maintain their houses to eastern societal standards in an economy that was increasingly restrictive. Each had to adapt to their surroundings, particularly in terms of food production, but especially while entertaining.

Colonel Lane, as commanding officer, seemed to feel obliged to entertain everybody who came to the post; and as our servants were inefficient and there was no market at hand, it was very difficult to have things always to please us, and I fear, to the satisfaction of our guests. [The] cook had rheumatism and was often “useless” so Mrs. Lane had to do much of the work.[xxx]

On their voyage from their previous assignment to Fort Union, the Lane’s cook was wed, much to the surprise of Lydia.

The cook, ugly as she was, won the hand—I cannot say the heart—of a stone-mason at Fort Union, almost immediately,—how, I never understood. She was old as well as ugly, and not at all pleasant-tempered, and, to crown all, a wretched cook. When she was disagreeable, she always showed it by reading her Bible—always a sure sign of ill temper with her. The man must have needed a housekeeper badly to marry old Martin. The nurse took her place in the kitchen. I had to teach her everything. We managed not to starve.[xxxi]

Reflecting on particularly eventful evening entertaining, Lane wrote:

One day I had cooked a dinner for a family of seventeen, including children. It was on the table, and I was putting the last touches to it preparatory to retiring to the kitchen. I could not sit down with my guests and attend to the matters there at the same time. I was stooping over to straighten something when I heard an ominous crack above my head, and, before I could move, down fell half the ceiling on my back and the table, filling every dish with plaster to the top. … Fortunately, I had plenty of food in reserve, and it was soon on the table.[xxxii]

Latinos at Fort Union— José and Haney:

Upon arriving at Fort Union, Lane added a servant and his daughter to her household. Both were New Mexicans. Lane recalls her time with them fondly:

We were quite at home in a short time, and, with the addition of a young Mexican man a little Mexican girl to our establishment, we were comfortable. The man milked the cows, brought wood and water, scrubbed floors, etc., besides telling the children the most marvelous tales ever invented. … The children understood his jargon better than I did and adored him. José was his name. My maid being English called him ‘Osay. She was an endless source of amusement to him, and he tormented her beyond endurance.[xxxiii]

Jose brought with him his daughter, Haney, who often played with the children of the Lane family. Lane recalled that “their language was a wonderful mixture of Spanish, English, signs, and nods, but each understood it perfectly.[xxxiv] After losing her cook to marriage and maid to rheumatism, Lane trained José to help in meal preparation and cleaning.

Lane recalled José as an oddity in the kitchen, his long black hair reaching down to his shoulder, covered with a felt military hat. He was unlike any cook she had had previously:

Early one morning I found him in the kitchen, deeply interested in preparing something for breakfast; his white shirt was outside of his trousers and hung far below his short blue jacket, which was ornamented with brass buttons. His high black felt hat was on his head as usual, ad below it streamed the coarse hair. I smiled at his absurd appearance, of which he was unconscious, going steadily on with his work. I had gone into the kitchen in anything but a gay mood, with the prospect before me of cooking breakfast for a number of strange people, but as the sight of José my spirits rose.[xxxv]

Narratives that highlight the humanity and that pin a specific identity to Hispanos at the Fort not only bring to life foodways but also help to fully frame the narrative of the fort. In limited cases, evidence of Hispanos can be seen in the physical remnants. Behind the post commander’s house is a corner fireplace in an outbuilding along the property wall (Fig. 15). It is reminiscent of local Hispanic building traditions and was likely the living quarters of servants like José and his daughter Haney. While accounts of New Mexicans are almost non-existent at the fort, the few that do exist like that of José and Haney must be interpreted.

Figure 15. Photograph of a corner fireplace at the post commanders house. Corner hearths like these are built in the local New Mexico vernacular and would likely have been used by servants living in out buildings behind the officers’ quarters. (Photo by author, 2018)

African Americans at Fort Union and Slavery

In the early years of Fort Union, prior to President Lincoln’s 1862 Emancipation Proclamation, there were slaves at the fort. Almost no record of these individuals exists. In the letters of Katie Bowen, only a few lines refer to her own servant, and even fewer refer to other slaves at the fort.

Margaret

One of the only accounts of slaves at Fort Union is found in the journal of Katie Bowen. When Bowen and her husband left for the fort, they took their slave Margaret with them. Due to the bias of any archive toward white stories, it is impossible to say how many slaves were at Fort Union in its early years. Margaret offers us a glimpse into the life of a slave, African American, and a cook at the Fort. While seated on her porch journaling, Bowen recounts an encounter with Margaret:

Margaret has brought me a plate of molasses candy and here I sit

rocking the cradle with one foot and employing my left hand to furnish my

mouth with candy. She is a very good girl and cooks nicely, as well as being an excellent house servant. She has all the care of the milk and butter making and I shall be sorry to part with her in case we move to a free state. Her mother is a free woman in Louisville and able to buy her, so if possible, we will carry her to her mother or set her free.[xxxvi]

On a different occasion, Bowen alludes to the presence of other servants, in addition to Margaret, that were also likely slaves:

Our servant is a host in herself and will sleep on the floor to keep fires for me. … A man comes every day to take care of the cows and the prisoners supply us with wood, so I think I am very well cared for.[xxxvii]

Several decades later, correspondence on the African American presence at Fort Union is even more limited. When seeking a replacement for her married cook, Lydia Spencer Lane recounts hiring a black woman on a trial basis for the position, “The only cook I could find to replace my sick one was a colored woman whose right hand was deformed. I tried her, but that hand, with her lack of cleanliness, was too much for me, and I concluded I would prefer to do all the work than have her about me and I sent her off.”[xxxviii]

Food as Dynamic Interpretation: How can food change site interpretation?

Recommendations:

1. Hold interactive interpretation cooking sessions on-site

a. E.g. Breadmaking at the bakery

i. Could include a bread trough and paddles to move or mix the dough with

2. Increase the number of pathways at the fort to reach spaces like the cellars of the post commander and quartermaster, the bakery, officer’s quarters, sutlers store, etc.

3. Create an optional off-path, ranger-led tour that takes visitors into the various rooms and buildings of the fort

4. Promote and interpret the known identities of cooks, servants, and officer’s wives—especially the underrepresented ones

a. Could provide optional “identities” to visitors of people like José, Margaret, or Lydia Spencer Lane, to better understand the social narrative of the fort

5. Create a more robust, many recipe cookbooks with maps that track the provenance of goods that can be taken home to continue the experience after leaving the fort

Conclusion

Throughout its history, Fort Union has defined and delineated the culinary landscape and the transportation of foodstuffs in the southwestern region. Decisions made by the fort about what to eat, how much to eat, who ate what, and who could access and distribute food defined the social and cultural dynamics of the region. Yet, at the same time, individuals including New Mexicans and challenged the established system, working alongside it to augment the culinary landscape. This study examines the peopled history of food at the fort. It offers a new interpretation of the lofty academic discussion of changing economies and markets by placing the discussion into something relatable and tangible: a recipe book and a visual map of foodways.

As an interpretive method, recipes, cooking, and mapping have the potential to address a significant, missing interpretive link at Fort Union in a way that all visitors can connect with. Food as interpretation challenges traditional National Park Service sign-board and ranger-led tours by engaging visitors in kinesthetic and sensory ways. The missing social narrative of the cooks, traders, and other individuals that dealt in food need to be interpreted in order to fully understand not only the narrative of Fort Union but also the region as a whole. Recipes are often passed from generation to generation, linked to the life and culinary habits of a family member. It is this intensely personal element of cooking that can frame Fort Union in a new way. Interpretation based on a firm understanding of food systems at the fort has the transformative ability to link social narratives to place and to create a new, dynamic, and engaged understanding of an important location in the history of the American We

Endnotes

[i] Darlis A. Miller ed., and Lydia Spencer Lane, I Married A Soldier (Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, 1987), 92-93. Found in Fort Union Fact File VC, folder MM55 Women’s Accounts from Fort Union.

[ii] Catherine Bowen, “My Dear Mother: the Letters from Catherine and Isaac Bowen, 1851-1853 from Fort Union, New Mexico Territory,” Arrott Collection, Donnelly Library, New Mexico

Highlands University, Las Vegas, NM.

[iii] Leo E. Oliva, Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest: A Historic Resource Study for Fort Union National Monument, (Sante Fe, NM: Southwest Cultural Resources Center, National Park Service, 1993), 17, https://www.nps.gov/foun/learn/historyculture/upload/TOME-2.pdf (accessed February 26, 2018).

[iv] Robert W. Frazer, Forts and Supplies: The Role of the Army in the Economy of the Southwest, 1846- 1861 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983). Darlis A. Miller, Soldiers and Settlers: Military Supply in the Southwest, 1861-1885 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989). Robert M. Utley, Fort Union National Monument, New Mexico (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1929), 50-54. Details the commissary and daily schedule of soldiers including meals.

[v] Oliva, Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest (Sante Fe: NPS, 1993), 57, 121, 654-655.

[vi] Joseph P. Sanchez et al. Fort Union National Monument Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, (Las Vegas, NM: National Park Service, 2006), 8, 10, 18-19, https://www.nps.gov/foun/learn/historyculture/upload/FOUN-Ethnographic-Overview-0106.pdf (accessed February 26, 2018).

[vii] Ibid., 58, 149, 228-234, 645. The post sutler is detailed on 149, 645. Farm detailed on 58, 228-234. Laura S. Harrison, and James E. Ivey, Of a Temporary Character: An Historic Structure Report and Historical Base Map (Sante Fe: Division of History, Southwest Cultural Resources Center, Southwest Region, National Park Service, Dept. of the Interior, 1993), 125-127.

[viii] Ibid., 125-127, 149-154.

[ix] Ibid., 131. Oliva, Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest (Sante Fe: NPS, 1993), 58, 228-234.

[x] Harrison, Laura S., Of a Temporary Character: An Historic Structure Report and Historical Base Map (Santa Fe: National Park Service, 1993), 25-27.

[xi] FOUN Fact File VC, Research notes for interpretive signboards.

[xii] Ibid. See also Combined Roster of Civilian Employees at Fort Union 1860-1867, Fort Union Library.

[xiii] Mrs. Orsemus Boyd, Cavalry Life in A Field Tent (New York: J. Selwin Tait & Sons, 1894), 204.

[xiv] Manual for Army Cooks (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883), 238-239.

[xv] Letter to Bvt. Col. T. F. Chalfin from 2nd Liet. A. R. King, September 28, 1869, Arrott Collection, New Mexico Highland University, volume 23, page 216.

[xvi] Thomas J Caperton and LoRheda Fry, Old West Army Cookbook 1865-1900 (Santa Fe: The Museum of New Mexico, 1974). Found in the Fort Union Library call number UC723,W4 C36.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Brevt Maj. and Asst. Surg. USA H. A. DuBois to Col T. F. Chalfin, August 29 1866. Arrott Collection, New Mexico Highland University, volume 18, page 18.

[xix] Oliva, Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest, 8.

[xx] Catherine Bowen, “Letters from Catherine Bowen, 1851-1853,” Arrott Collection, Volume 28, page 52.

[xxi] Lydia Spencer Lane, I Married A Soldier, 146. Found in Fort Union Fact File VC, folder MM55 Women’s Accounts from Fort Union.

[xxii] Bowen, “Letters,” Sep 2 1851.

[xxiii] Charlotte Sibley, 2. Found in Fort Union Fact File VC, folder MM55 Women’s Accounts from Fort Union.

[xxiv] Bowen, “Letters,” Nov. 30 1851, 15.

[xxv] Lili Spaulding and John Spaulding, Civil War Recipes: Recipes from the Pages of Godey’s Lady’s Book (Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, 1999), 25.

[xxvi] “Saleratus to Baking Soda,” Baking Techniques, History, & Science, https://joepastry.com/2011/saleratus-to-soda/.

[xxvii] Bowen, “Letters,” Nov. 28 1852.

[xxviii] “Oven,” Fort Union Library Files, Fort Union National Monument, 9/15/1967.

[xxix] “Ice Pond, 1870,” Fort Union Library files, January 1967. From Surgeon General’s Inspection Report, 1870.

[xxx] Lydia Spencer Lane, I Married A Soldier, 145.

[xxxi] Lane, I Married A Soldier, 131.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] Ibid., 143-144.

[xxxiv] Ibid., 143.

[xxxv] Ibid., 145.

[xxxvi] Bowen, “Letters,” Feb. 28, 1852, 24.

[xxxvii] Ibid., Feb. 2, 1852, 22.

[xxxviii] Ibid., Lane, I Married A Soldier, 146.