the elizabeth harper kay house

227 East High Street, Philadelphia, PA

Philadelphia Register of Historic Places Nomination (Draft)

Summary

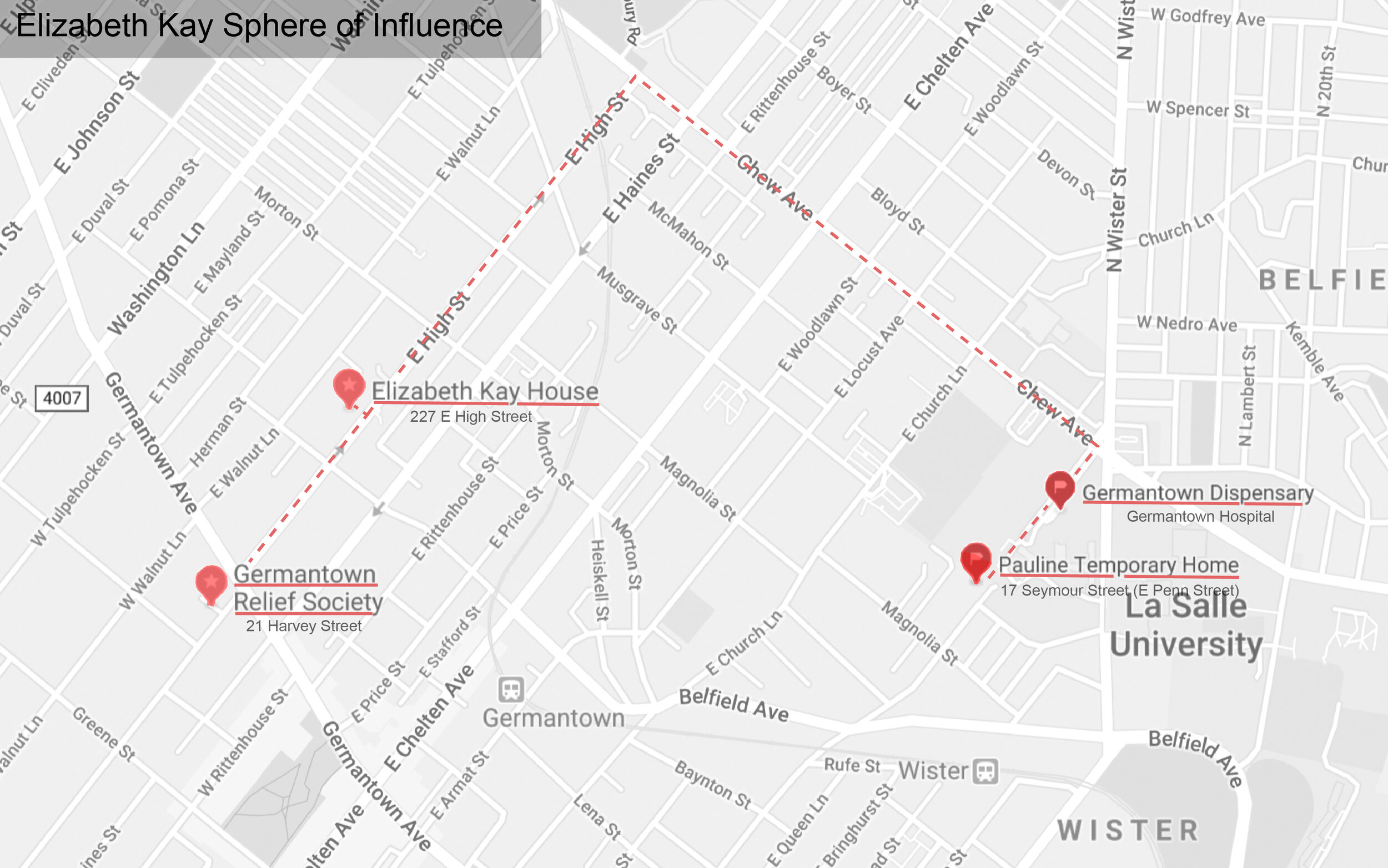

The Elizabeth Kay House, located at 227 East High Street in the Morton Neighborhood of Germantown, has a rich and layered history that parallels the early rise of organized charity and philanthropy across the United States. Locally famed architect George T. Pearson designed and built the house in 1885 for Elizabeth Kay, whose family made their wealth from publishing. Elizabeth Kay was a celebrated charity worker who helped found the Women’s Auxiliary Board of the Germantown Relief Society—the first society for organizing charity in the United States. Kay’s attitudes and ideas of the poor closely reflected the ideals of reform and charity that were emerging at the time amongst the upper class. Kay, like many wealthy women, did not marry, choosing instead to devote her life to the reform of society. She was the first volunteer visitor for the Germantown Relief Society and her efforts brought her in close contact with other similar charities. She fought to remove children from almshouses by founding the Pauline Temporary Home and even housed several children in her own house on High Street. Across from the Pauline Home, Kay volunteered as a visitor for the Women’s Dispensary in the Germantown Hospital. 227 East High Street was the lifelong base of operations for Kay’s charitable efforts and is significant as a reflection of her life and charitable works.

Criterion of Eligibility:

· Criterion A- Association with the life of a person significant in the past: Elizabeth Harper Kay

· Criterion E- Association with architect George T Pearson as an example of his eccentric work

Period of Significance: 1885-1914

Built: 1885 for Elizabeth H Kay

Architect: George T. Pearson

Style: Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, Tudor & others

Architectural Description

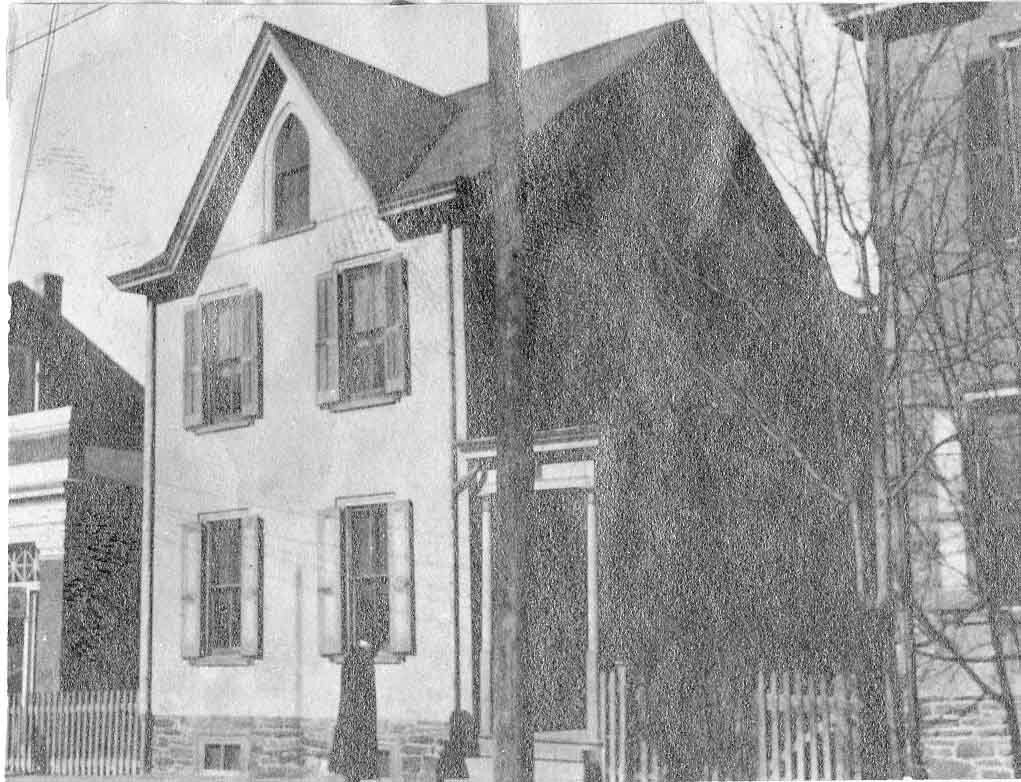

The Elizabeth Kay House, located at 227 East High Street in the Morton neighborhood of Germantown, Philadelphia, was built for Elizabeth Kay around 1886. The building is located on High Street, an early suburban railroad development between Baynton Street and Morton Street. It is one of several architect-designed properties that line the street. Many of the surrounding houses are large suburban starter villas from the same era of construction. The Elizabeth Kay house is a two-and-a-half-story building and measures 30 feet wide on the façade.

Famous local architect George T. Pearson constructed the property in a hybridization of styles. 227 East High Street combines elements of the Colonial Revival, Tudor, Queen Anne, and even Romanesque styles into a highly synthetic and eclectic design. While the building’s original design has been altered somewhat, it maintains most of its character-defining features and maintains excellent integrity.

227 East High Street is one of many suburban mansions built along High Street for wealthy residents of the area. The wider street retains and steep setbacks of the house retains a parkway feel.

The house’s façade overlooks East High Street to the southeast and is asymmetrical, with its entrance recessed and set back from the main massing of the building on the northeastern side. The majority of the façade is covered in rough coursed ashlar Wissahickon schist. A large semicircular front porch divides the façade and projects outwards towards the street. A cut bluestone belt course and coping further divides the stone façade just below the parapet and attic window. The façade is divided into three parts: the porch (1st story), bay window (2nd story), and attic story (2 ½ story). The roof of the building is asymmetrical and cross-gabled. The façade projects upwards and is corbeled outwards, forming a shaped parapet that gives the house a baronial fortress feel.

The main entryway and side portion of the building is set back from the façade. Steps lead up to the door and entryway, which is set in a deep recess below a curved arch. Above the entry is a small window with an ornamental muntin ogee arch and a bluestone sill, with a segmented stone jack arch above.

The ground floor division, the porch, divides the façade into the first third and is constructed of wood trim with a patterned wood ceiling on the underside and asphalt shingles on the roof. Four pairs of Tuscan columns support the semicircular structure. Between the ground and columns is a modern wooden lattice. There is a large French door in the center of the porch that is flanked by two sidelights and white wood paneling. A pair of windows rests above the sidelights and is composed of square and diamond muntins in an octagonal Chippendale pattern.

Projecting out of the building’s façade on the first floor is a bay window. The bay window is composed of four-over-one windows on the sides and one eight-over-one window in the center. Each window is replacement sash. Above the windows and below the roof is a carved wooden Romanesque foliate with a floral pattern. The bay window rests on the porch below and both elements are centered on the façade.

The attic story is characterized by two belt courses above and below a window that divides the triangular space. Between the two bluestone belt courses is rough faced stone, the same as the rest of the façade. Centered in this section is a six-over-one replacement sash window with a beaded keystone and jack arch above. Between the peak of the parapet and the top belt course is white stucco, indicative of an area that likely was once tile-hung terra cotta, similar to those found in the gables on the side of the house. The parapet above is trimmed with curved bluestone trim and decorated with a diamond shaped stone at its peak.

The Elizabeth Harper Kay House retains excellent integrity due to the relatively few significant alterations to its original design. The house maintains integrity of location and setting, as the building has never been relocated. While the façade is missing some original features, it maintains integrity of materials and workmanship, largely due to the existence of the original masonry patterns and visual organization. 227 East High Street retains integrity of design as it still closely follows the designs of George T. Pearson, readily conveying the eccentricity of the architect and maintain integrity of feeling and association. The Elizabeth Harper Kay House, at 227 East High Street, retains excellent integrity and readily conveys all seven aspects of integrity.

Significance Narrative

Summary Paragraph

The Elizabeth Kay House, built at 227 East High Street, has a rich and layered history that parallels the early rise of organized charity and philanthropy across the United States. Locally famed architect George T. Pearson designed and built the house in 1886 for Elizabeth Harper Kay, whose family made their wealth from publishing. The building is significant under Criterion A for its association to life and works of Elizabeth Harper Kay, and under Criterion C and Criterion E as an example of the eccentric style and works of architect George T. Pearson.

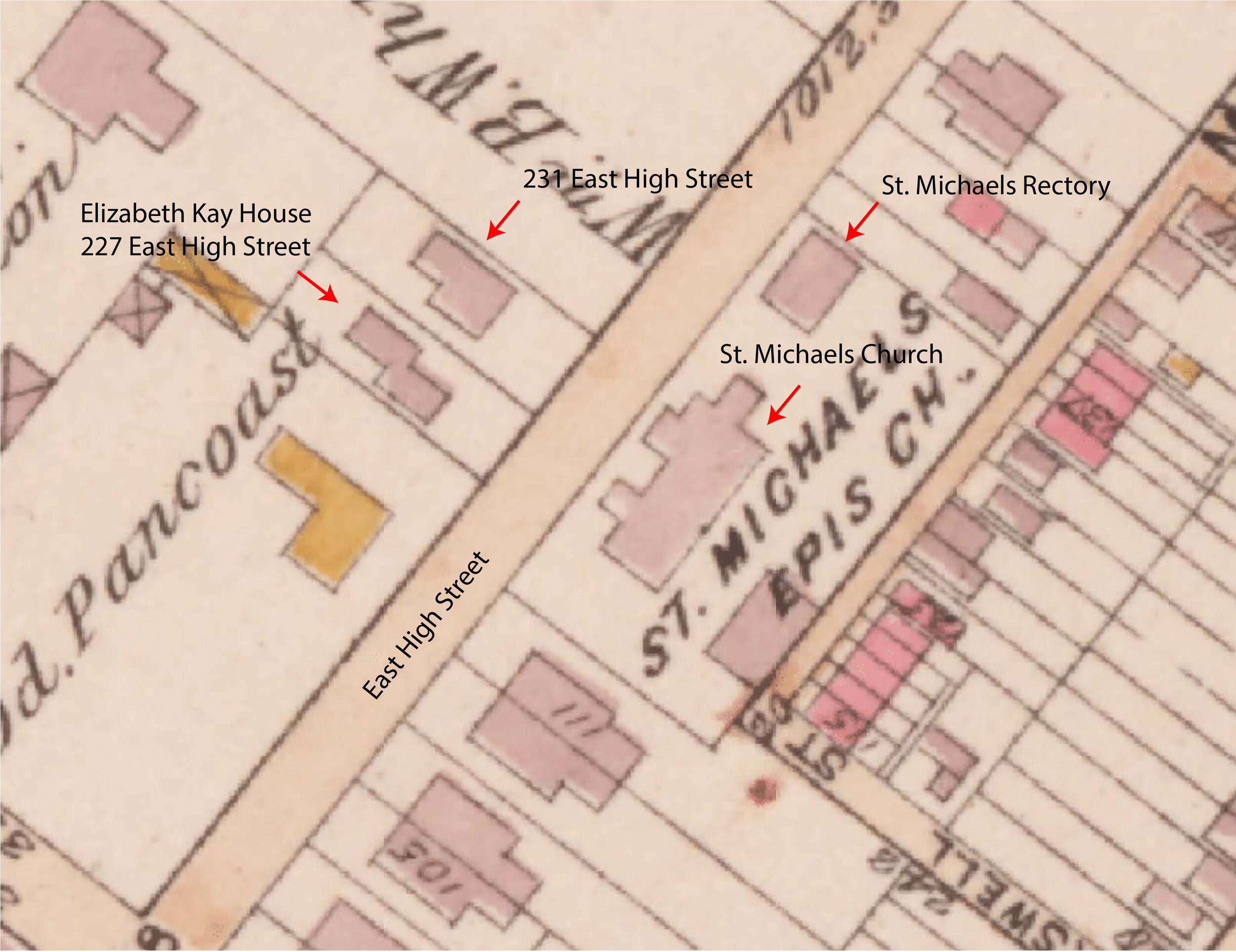

As a longtime Germantown resident and architect, George T. Pearson and his works forever changed the landscape of suburban real estate development in Germantown. His mastery of multiple styles allowed him to readily and freely borrow elements from one style and to pair it with another. His designs can be found across the borough and City of Philadelphia, but one of the highest concentrations of his work is found along High Street where he designed multiple houses and buildings (Figure 1). 227 East High street is an excellent example of his architectural legacy in the Morton Neighborhood of Germantown.

Elizabeth Kay was a celebrated charity worker who helped found the Women’s Auxiliary Boards of the Germantown Relief Society—the first society for organizing charity in the United States. Kay’s attitudes and ideas of the poor closely reflected the ideals of reform and charity that were emerging at the time amongst the upper class. She was the first volunteer visitor for the Germantown Relief Society and her efforts brought her in close contact with other similar charities. She fought to remove children from almshouses by founding the Pauline Temporary Home and even housed several children from almshouses in her own house on High Street. 227 East High Street was the lifelong base of operations for Kay’s charitable efforts and is significant as a reflection of her life and charitable works.

Criterion D and E: George T. Pearson—Architect and Master of Styles

George T. Pearson: An Architecture of Eccentricity

George T. Pearson, a relatively unknown architect may have disappeared into obscurity, but his unusual works define the neighborhoods of Germantown and readily stand out among their neighbors. Pearson opened his office in 1880 and subsequently designed works across Philadelphia and Germantown, but is not in the cannon of notable architects of the time, that included, among others, Frank Furness and Samuel Sloan.[1]

Pearson was born on June 7, 1847 in Trenton, New Jersey. Following his schooling at the Trenton Academy and New Jersey Model School, Pearson sought out an apprenticeship to architect Charles Graham.[2] The firm of C. Graham & Son operated out of Elizabeth, NJ and is noted to have worked largely in New Jersey and New York.[3] Graham is believed to have started as a “stair trimmer and house builder,” but like many builders of his time, decided to later market himself as an architect.[4]

In 1872 Pearson became a draftsman for Addison Hutton, who “was one of the principal architects of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century,” and moved to Philadelphia.[5] Hutton formed a partnership with celebrated architect Samuel Sloan from 1864-1868, called Sloan & Hutton, but later parted with the architect and went on the forge his own highly successful career.[6] Following his fruitful work with Hutton, George Pearson opened his own firm in 1880 in downtown Philadelphia. While Pearson worked in Philadelphia, he resided in Germantown at 124 West Walnut Street, one street northwest of High Street.[7] Pearson was a member of the American Institute of Architects and the T-Square Club and died in 1920. His most noted work is the house of John B. Stetson, the manufacturer of the famous cowboy hats.[8]

Architectural Patronage and the High Street Houses of George T. Pearson

227 East High Street and its eclectic hybridization of styles catches the eye of those driving and retains significant integrity of its original design (Figure 2). It is impossible to define a single style for the house—one can assume, much to the pleasure of Pearson, who reveled in his free use of architectural elements across his works. Upper middle-class, individualistic houses on High Street are common; often these houses were designed along the lines of one or two styles. However, 227 East High Street is one of several Pearson Designed works that maintain this notable exception and convey the importance of Pearson’s work in altering the landscape of High Street at the turn of the century.

The Elizabeth Harper Kay House at 227 East High Street was commissioned by Elizabeth Kay in 1886, but the commission is only listed to be made of stone.[9] It is impossible to determine the intentions of Kay’s commission or the type of house she had hoped to design by hiring architect George T. Pearson. However, the proximity of Kay’s house to other Pearson works can perhaps offer some insight. The Gummey family, whose real estate holdings along High Street placed them in a prominent position during its development, had a close connection to George T. Pearson. Elizabeth Gummey, the then late widow of John M. Gummey, a real estate investor and founder of J. M. Gummey and Sons, purchased the property in 1885 and subsequently commissioned architect George T. Pearson to build her a substantial house at 231 East High Street (Figure 5).[10] Previously, Gummey had lived at 183 High Street, but perhaps due to her husband’s death, downsized to a smaller house along the same street on the new lot. A year later in February 1886, Elizabeth Gummey split her land in half and sold the southern half to Elizabeth Kay. While Gummey’s house was built for Charles Gummey, her son, he never lived there and died in 1898. Elizabeth Gummey lived in the house with her two daughters until her death.[11] While no concrete connection has been found between Kay and the Gummey’s, it is easy to infer that the two were in contact with one another in regard to their choice of architect.

This relationship is most evident in the close proximity of both 227 and 231 East High Street to St. Michaels Church across the street. The Gummey family, wealthy patrons of the church, knew of George T. Pearson’s earlier work on the church rectory in 1880-1881.[12] Evidently satisfied with the work of Pearson on the church rectory, the Gummey family commissioned him to design their own Queen Anne home. There are many visual similarities between the two structures that highlight the evolution of the architect’s work including the use of similar materials and polychromatic coloring on each (Figure 5, Figure 6).

An Architecture of Conversation: 227 and 231 East High Street

While 231 and 227 East High Street were built a year apart, upon closer inspection, the two properties appear to be in conversation with one another. The heavy baronial fortress-like nature of the Elizabeth Kay House stands in stark contrast to the much lighter delicate nature of the Elizabeth Gummey House. One, in many ways, is masculine and one is feminine. The fortress-like, heavy, splayed foundation of 227 East High Street is echoed in the stepped-out, battered lower-level of 231 East High Street (Figure 7, Figure 8). Similarly, the incised rosettes on the bargeboards of the almost Jacobean gable of 231 East High Street (Figure 9a, Figure 9b), are echoes in reverse on the bargeboards of the gable on 227 East High Street. The relationship between the two is most clear in the repetition of same building material, tile-hung terra cotta, in the gable of each house.

The style of each is impossible to define, but if individual styles were to have opposite pairings they could be found in the differences between the two houses. Each share common elements of the same styles, but chooses opposite elements from each to contrast with the other. Colonial Revival and Queen Anne elements are common between the two but on opposite ends of the spectrum. Where each differs is on the distinctive styles Pearson draws on to contrast each house. 231 East High Street draws on the Jacobean Revival style in its chimney and thin masonry elements. While 227 East High Street draws on the heavy elements of Romanesque architecture and the baronial aspects of the Tudor Revival. In any case, it is clear that Pearson designed each of the houses to be in conversation with one another.

Criterion A: Elizabeth Harper Kay— Charity and Reform

Criterion A: Association with the life and works of Elizabeth Harper Kay (b. 1837- d. 1914), a person significant in the past.

Elizabeth (Lilly) Harper Kay was perhaps the most prominent individual to live at 227 East High Street and the property is significant under Criterion A for its association with her life and charitable works. 227 East High Street was Kay’s lifelong base of operations for her charitable efforts and is significant as a tangible environment in which to understand her life and the lives of women like her. Kay’s attitudes and ideas of the poor closely reflected the ideals of reform and charity that were emerging at the time amongst the upper class. Women, like Kay, found themselves with increased leisure time and a desire to become more involved in political and public arenas.

Elizabeth was one of the founding members of the Women’s Auxiliary Board of the Germantown Relief Society, the first organization in America to systematize and organize the distribution of charity.[13] She was the Society’s first volunteer visitor and influenced the ways in which charity was administered across Philadelphia. Elizabeth was also a founder of the Pauline Home for Children, an organization that sought to prove that children could be kept outside almshouses.[14] Elizabeth even housed children in her own home at 227 East High Street to demonstrate her own belief in this cause. Kay also served on the Board of Lady Visitors of the Germantown Hospital, aiding the sick and institutionalized.[15] Kay never married or had children, focusing rather on helping the poor through her charity work. In 1914 Elizabeth Kay died peacefully in her home at 227 East High Street, where she had spent her life helping those less fortunate.

The Kay Family: 1821-1914

Kay’s mother, like Gummey, was a widow. She was married to John Ippotsen Kay and together they had four children: John, Florence, Nannie, and Elizabeth Kay.[16] However, John, the younger, died at a young age leaving the family with only daughters. John Ippotsen, the father, married Elizabeth Harper, the mother, on January 1, 1833. John was one of nine children born to Reverend James A. Kay and Hannah Ibbotsen Kay of England. Reverend James Kay studied at Rotherham College in England and was well educated. However, James felt that his family needed greater religious freedom and decided to leave England. In 1821 the Kay family immigrated to the US aboard the Halcyon out of Liverpool, arriving in Philadelphia and settling in Northumberland, Pennsylvania and eventually working their way to Germantown.[17] James and his brother John, the uncle and father of John Ippotsen Kay, started Kay & Brother a publishing and bookselling company, which John Ippotsen Kay worked for later in life.[18] The company was located at 609 Otis Street, near the intersection of present-day Germantown Avenue and North 6th Street, and was likely the source of much of the Kay family fortune. John Ippotsen Kay died in 1859.[19]

According to the 1870 census, Elizabeth Harper Kay lived at 5056 Germantown Avenue with her mother Elizabeth, and two younger girls Meta Kay and Charlotte Burroughs, both in school aged 18 and 8 respectively. The family had two domestic servants Eliza Augustus from Pennsylvania and Margaret Dolan of Ireland.[20] Ten years later in 1880, Elizabeth and her family still lived at 5056 Germantown Avenue, but the young children staying with her had changed. Meta and Charlotte were no longer living there, but Marcelle and Annie are listed as adopted daughters. Marcelle was from France and Annie was from Rhode Island, and they were one and eighteen respectively. The increase in household members necessitated an increase in household staff. Three servants, Eliza Farrell, Mary Farrell, and Suzan Davis, all black, lived and worked with the family. According to the same census, Kay was worth $50,000 and held $4,000 in property, a substantial amount of money at the time.[21] This fortune allowed Elizabeth Kay to purchase land from Elizabeth Gummey in 1886 and to commission architect George T. Pearson to build a house for her at 227 East High Street.[22].

But this phenomenon of single women was hardly uncommon along High Street. Following her mother’s death, Elizabeth (formerly Lilly) assumed her mother’s name Elizabeth Harper Kay and lived in the house until her death in 1914. Elizabeth (Lilly) never married and lived in the house with her sister Annie, who also never married. In her old age, Elizabeth hired a cook by the name of Ellen Biscoe of Maryland to help her.[23] The Gummey family, right next door, had much the same arrangement. Elizabeth Gummey lived in her house with her two daughters until her death. Many of these women worked with local community organizations, churches, and other charities. Elizabeth Kay was one of these people, devoting her life to service and charity work.

Context: Women and Reform

At this time, amongst the middle and upper class, there was a strong desire to reform and remake society. Women fought to create for themselves new lines of work, forever redefining the role of women in society—especially the role of single and widowed women.[24] Volunteer organizations afforded women the opportunity to enter public and political realms previously dominated exclusively by men. As one scholar notes, “It was a man’s world, but women shaped it.”[25] The Industrial Revolution had created a newly wealthy middle and upper class that were substantially better off than many in Philadelphia.

Women of these groups had more choice than ever before at the turn of the century.[26] The last decades of the nineteenth century constituted an era of reform for causes across all aspects of society. Perhaps the best way to understand the vastness of charitable efforts during this period is to think of these networks as a charitable landscape. Women often worked in several different charities at one time. Organizations emerged for the reform of policemen, the criminal and insane, orphanages, and even the drunk.[27] Special attention was paid to the raising of children, especially young men.

Women, like Kay, recruited for their causes across groups, as these networks, these landscapes, were intimately linked. Many of the same women that worked in one charity did so in others. Organizations, like the Association for the Advancement of Women, connected these groups to national reform efforts and legitimized their work.[28] National organizations, like the Association for the Advancement of Women, provided local groups with access to the writings of prominent women including Professor Maria Mitchell and Julia Ward Howe who were members of the organization’s standing committee.[29] Seven women of Germantown, including Kay, were members of this organization—most notably Fanny B. Ames the wife of Reverend Charles Ames who developed the plan for the Germantown Relief Society.[30] Fanny B. Ames advocated for the removal of children from almshouses and was one of the founders of the Children’s Aid Society.[31] Connections like this reveal that many of these women, like Kay and Ames, were in touch across with one another charitable causes.

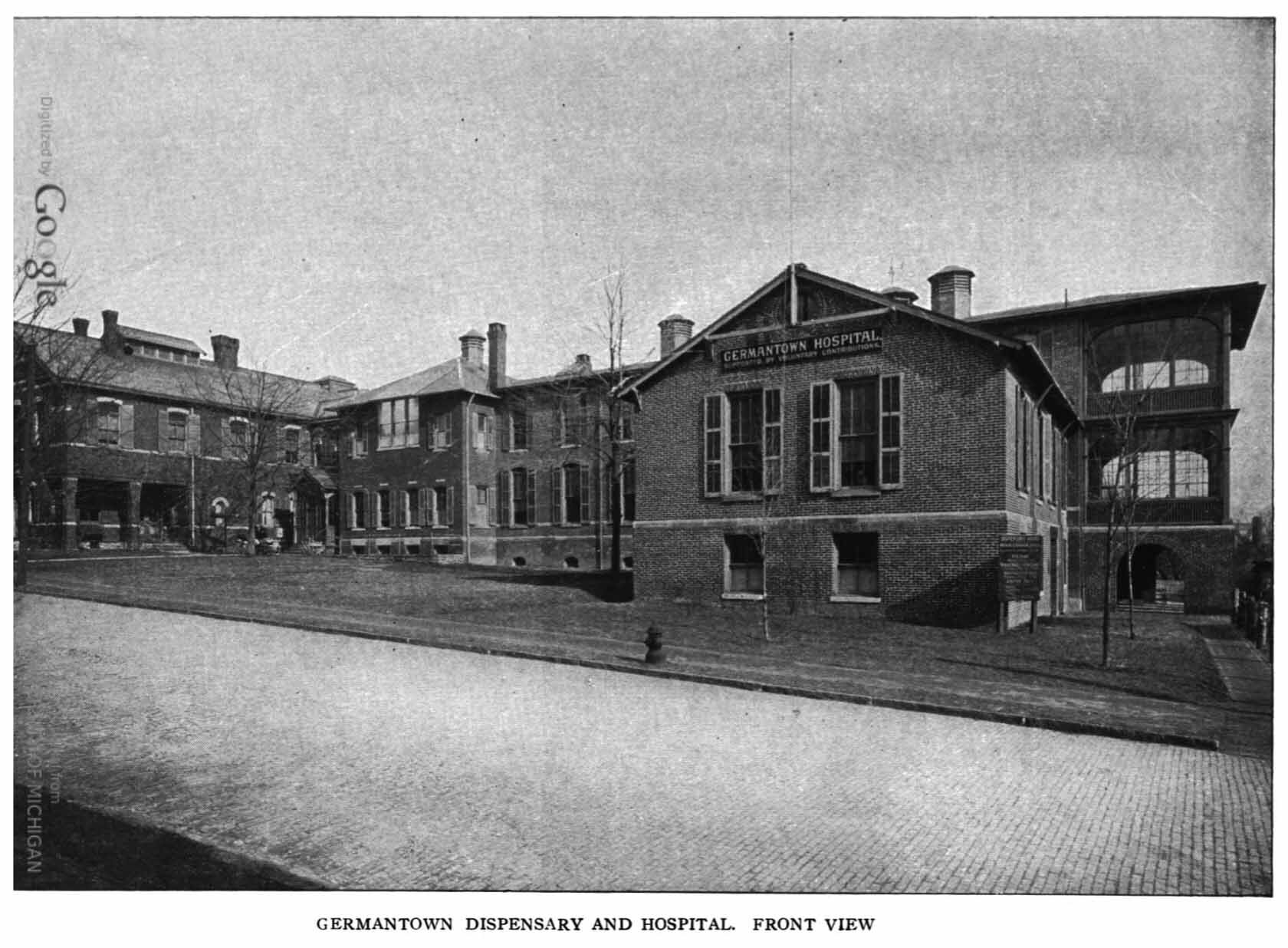

The Early Years: Kay and the Germantown Hospital and Dispensary

While it is impossible to say when and how Kay found her beginnings in charity work, her earliest recorded work was on the board of Lady Visitors for the Germantown Hospital and Dispensary (Figure 10). There is a strong possibility that other family members may have helped Kay to get her start in charity work. In the records of the Germantown Hospital, early significant donors include a J. Alfred Kay and a Mary Kay active around the same time as Elizabeth, likely cousins of hers.[32] In any case, “Miss Kay,” as she is referred to, served on the Board of Lady Visitors from 1873-1879, beginning her work just prior to the founding of the Germantown Relief Society.[33] However, it is likely that she served in other capacities at the hospital, before joining the board since she is listed as a donor to the hospital several years prior.

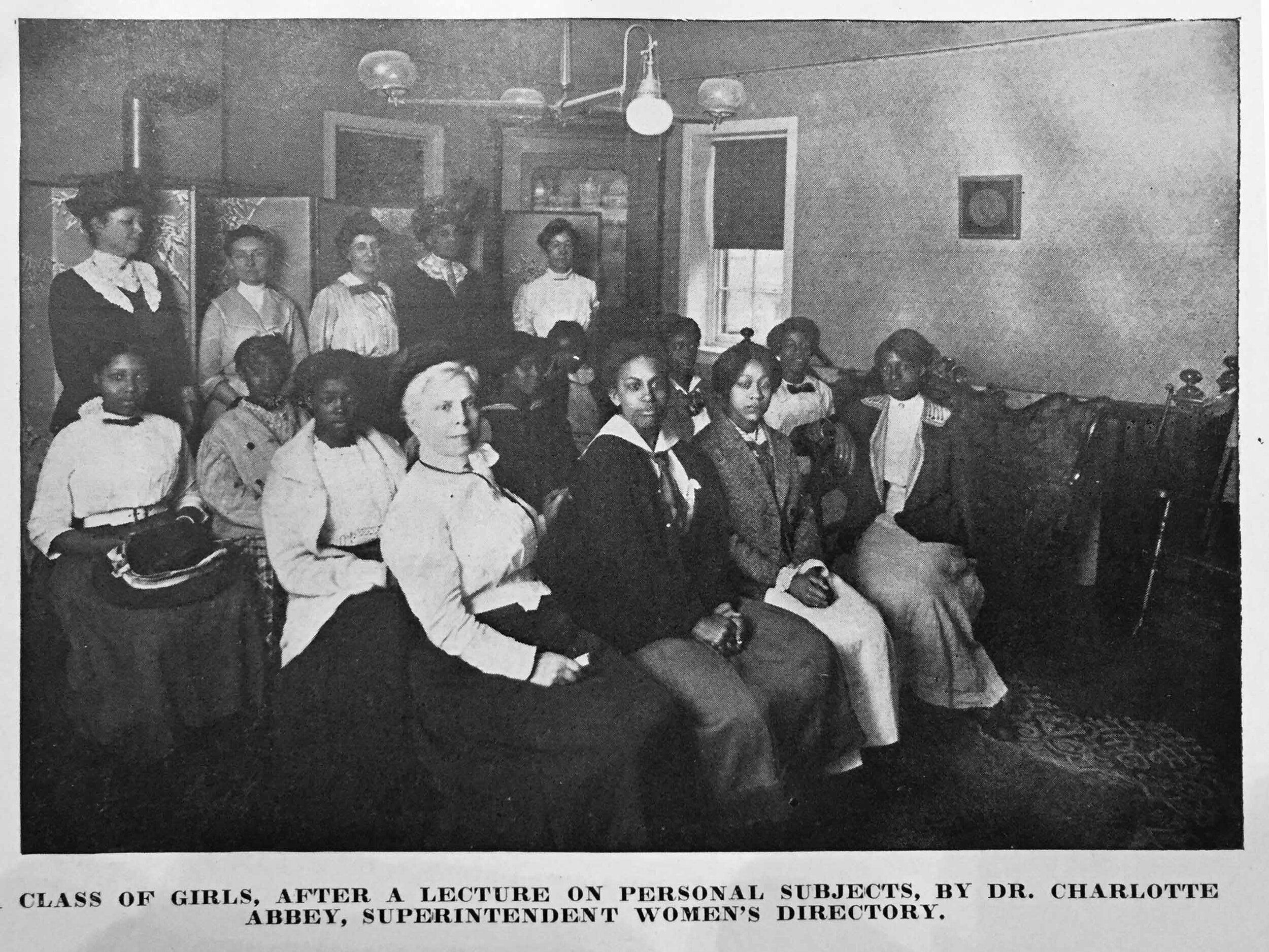

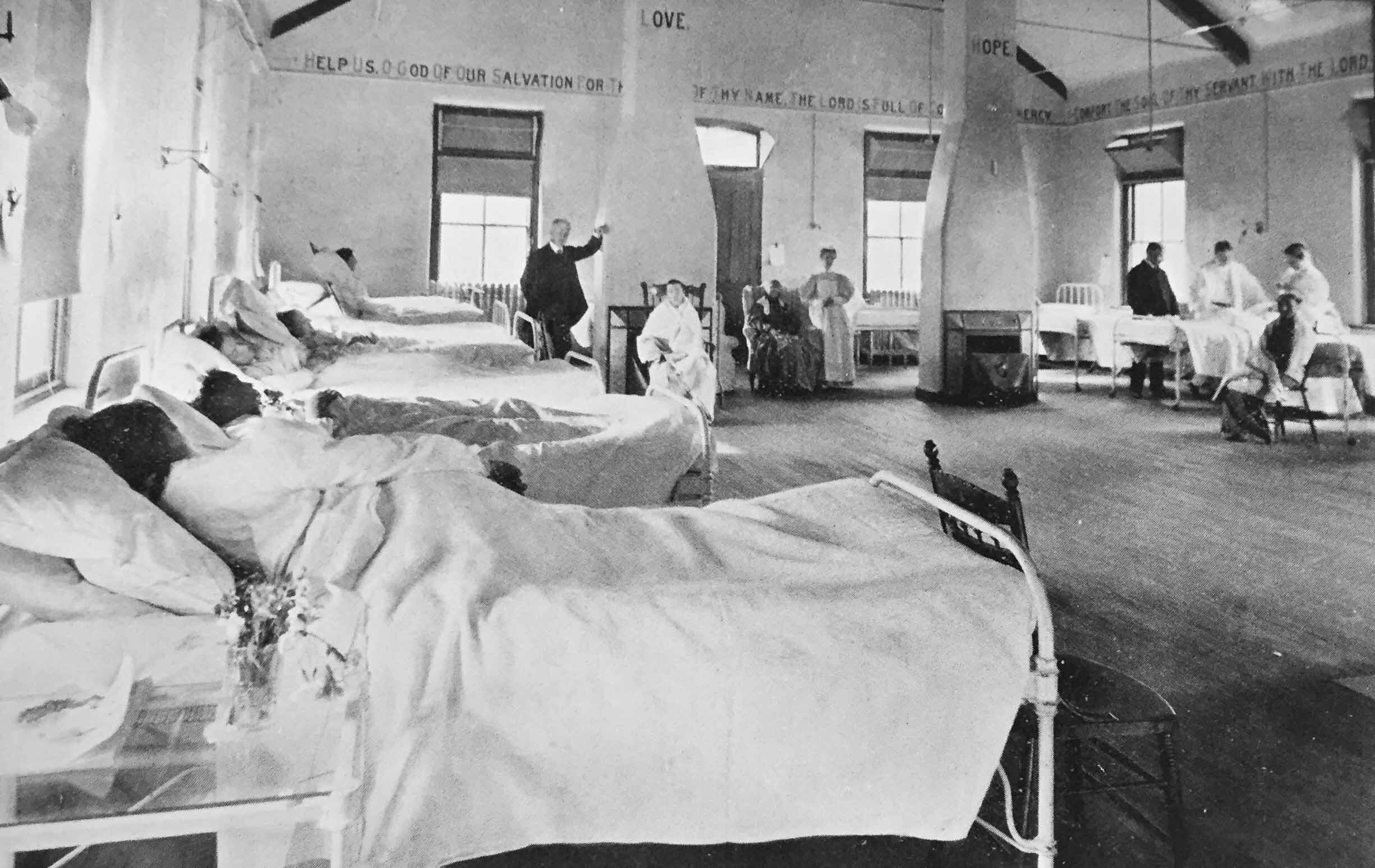

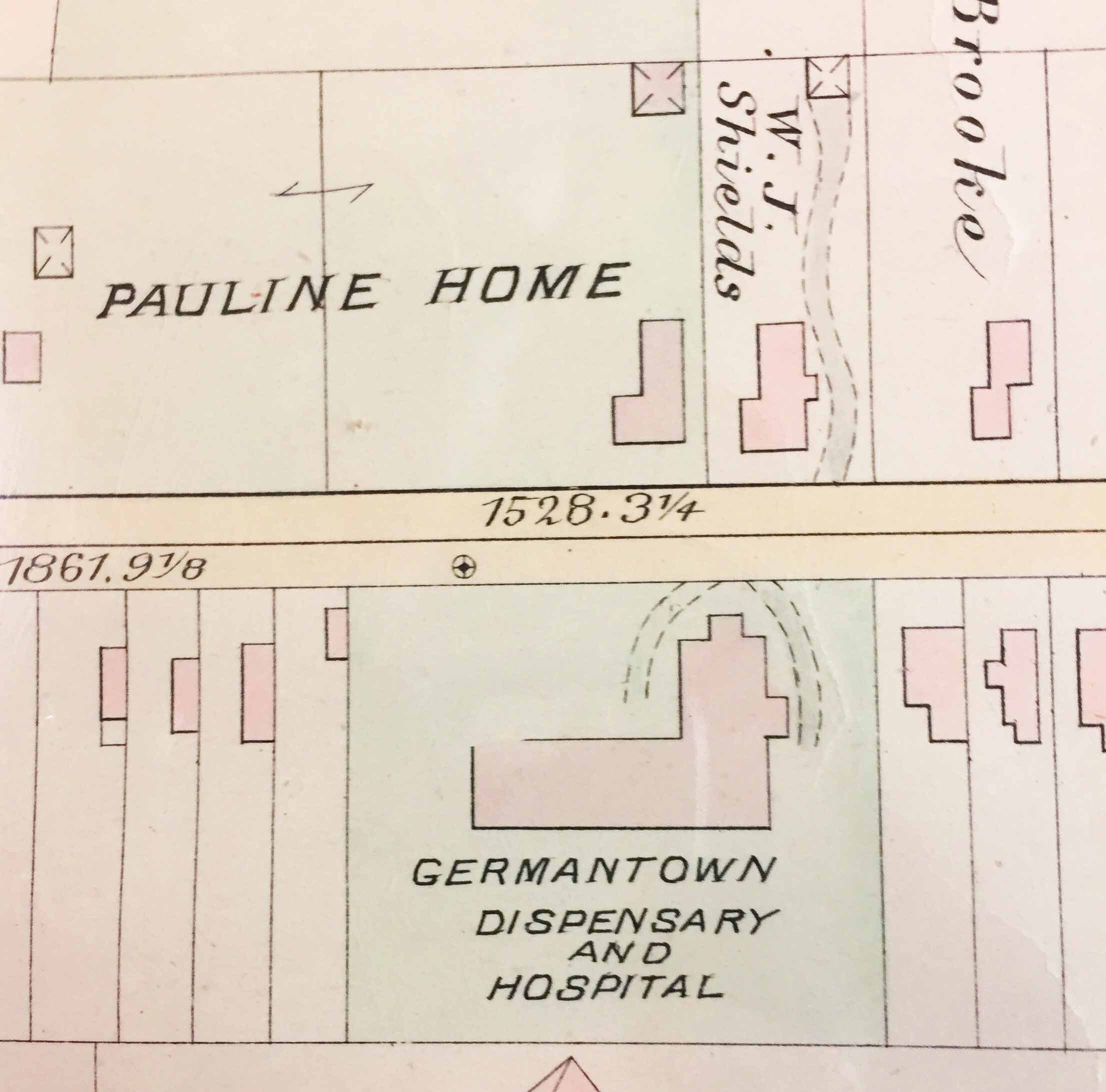

Lady Visitors, like Elizabeth Kay, tended to the sick and institutionalized, comforting and socializing with patients in the various wards of the hospital. Special attention was paid to the women’s and children’s wards by the visitors (Figure 11, Figure 12). However, what the Board of Visitors was most instrumental in doing, was organizing annual donation days, in which visitors asked the community for clothing, provisions, and money to furnish additions and new wards of the hospital.[34] Donation days were crucial to the success and efforts of the hospital. While little is written about their Lady Visitors, it is clear in the few references that do mention them that they played an essential role in the development of the hospital. It was here that Elizabeth Kay likely developed her interests in charity work that would later be reflected in her work with the Pauline Home across the street, as well as the Germantown Relief Society (Figure 13).

The Germantown Experiment and Charity Organization in the United States

Following the financial blunders of Jay Cooke, a wealthy financier, in 1873, Philadelphia, including Germantown, fell into an economic depression. Factories closed, and unemployment and poverty soared.[35] This financial crisis found its roots in the industrial revolution and the resulting increase in the urban population. In 1884 35% of the population of the east coast was estimated to be found in cities.[36] Backdoor calls for charity at the homes of the wealthy increased as a result and it became clear to the citizens of Germantown that a method for organizing and distributing charity was needed. Up to this point, beyond the almsgiving of churches, no charitable organization existed to administer aid.[37] Seldom did churches communicate with one another, so it was possible for individuals to work the system to their advantage, creating what many saw as professional pauperism. Well-indented aid was wasteful.

In 1873, Samuel Emlin, a prominent Germantowner, called for plans to establish a system in Germantown to address these issues. The meeting was well attended, but the only person that came with a plan was the Reverend Gordon Ames of the Unitarian Church of Germantown.[38] Ames was an avid reader and was familiar with the works of Thomas Chalmers and Octavia Hill of London, as well as a German method of aid called the Elberfeld System of Poor Relief.[39] Ames’s plan, based on these precedents, called for the division of the ward into eight districts, a central office with a paid superintendent who investigated applications for aid, and a corps of friendly visitors who would administer and befriend those in need. No aid was given without a proper and thorough investigation of each case. Once each case was investigated, the Society made the distinction between the “worthy” and “unworthy” cases, administering aid in kind. The Germantown Relief Society as it came to be known, was the first society for organizing charity in the country.[40]

While the Germantown Relief Society was arguably the first of its kind in the country, it was not citywide; it administered only to the 22nd ward. Buffalo, New Haven, and Boston are widely considered to have developed the first city-wide societies for organizing charity, notably after the Germantown experiment of 1873. But the impact and legacy of this experiment were felt nationwide, especially in Philadelphia with the subsequent founding of the Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charity in 1878 along the same model as the Germantown Relief Society.

Each of these early charity organizations shared many of the same guiding principles. Two dominant systems prevailed: the London System championed by Octavia Hill and others, and the Elberfeld System founded in Germany. Each has been referred to respectively as the “case system” of assigning visitors to individual cases vs. the “space system” of assigning visitors to distinct regions. Ultimately, the case system championed by the Buffalo Society won out. The Buffalo system used individual casework assigned at a centralized office, versus the geographic system of Philadelphia and Germantown in which visitors were assigned to distinct regions. The Philadelphia system, it was found, created districts of immense need in impoverished areas and areas of relatively little strain in wealthier parts of the city. Nonetheless, the Germantown system of organizing charity played an important role in the history of welfare and social work. The method for organizing charity that was pioneered in Germantown by organizers like Ames and by visitors like Kay became the model for other cities across the country. In 1893 the charity organization movement was at work in 92 cities, but in 1900 it “dominated American philanthropy.”[41]

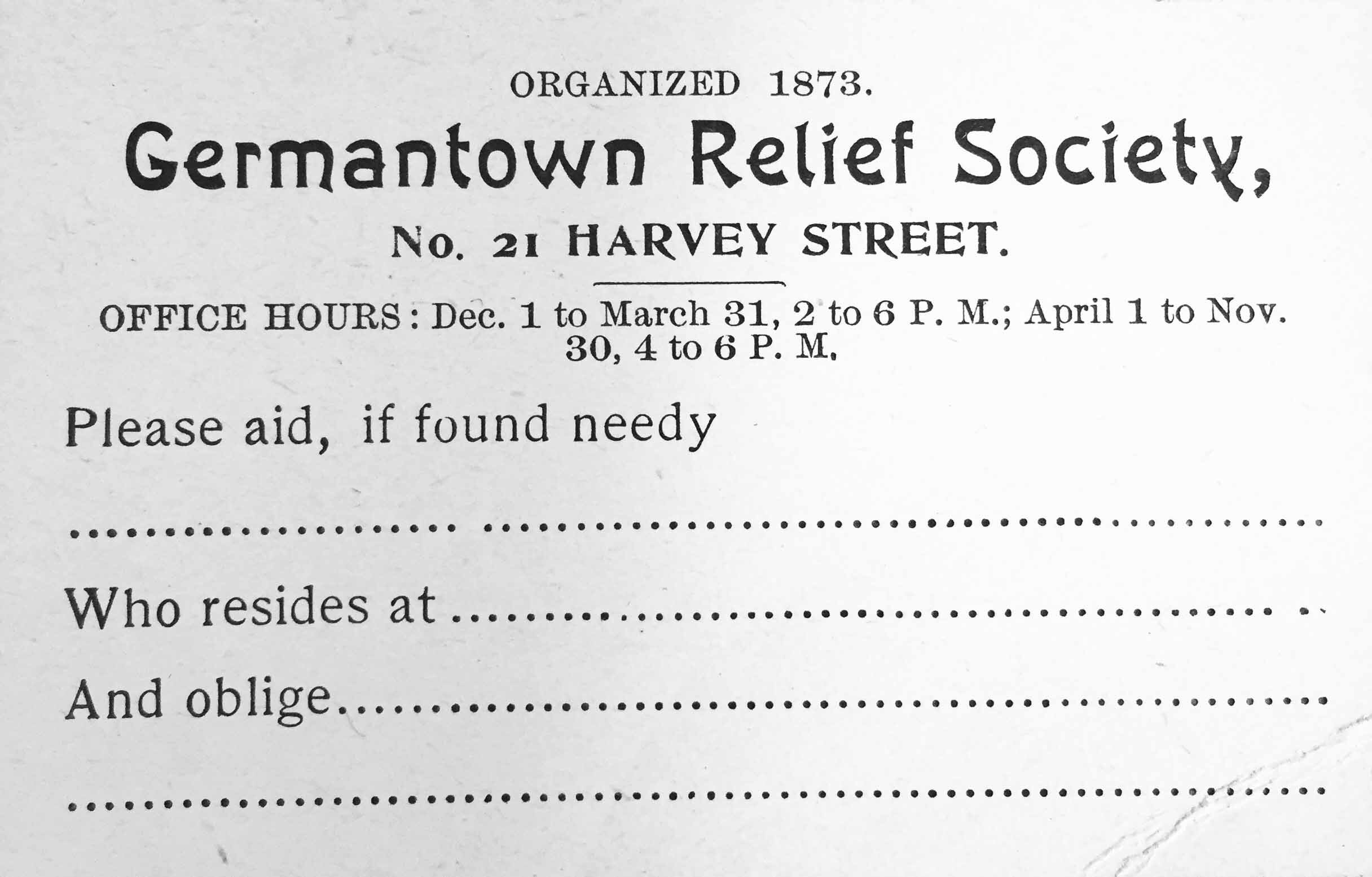

The Germantown Relief Society and Friendly Visitors

Kay was known best in Germantown for her work with the Relief Society, where she was noted as “a familiar figure on the streets of Germantown wending her way to the homes of the poor,” and that “her personal ministrations to the needy, sick ceased only when her health failed.”[42] The Germantown Relief Society, founded in 1873, sought not only to help the destitute, but also to root out the causes of poverty. The formation of the organization fits in with dominant ideas of reform common at the time. However, as the organization is quick to note, there were too many small individual charities available in the area. The founders worried that the abundance of small charities and the lack of coordination amongst them was the cause of professional pauperism and the door to door begging that was prominent in the area at the time. To solve this problem, the Board of the Germantown Relief Society came up with a unified system in which a person who encountered an individual in need could give them a card to refer them to the Society instead of money (Figure 14).

Once these individuals came under the purview of the Relief Society, a female Visitor, who monitored and maintained personal connections with each family, visited them regularly.[43] Notebooks kept at the Germantown Historical Society detail many of the homes that visitors like Kay attended to along Mechanic Street and Centre Street (Rittenhouse) among others.[44] She was later the president of the Women’s Board and Chairman of the Relief Employment Committee for the duration of her life, Kay was listed as an Honorary Board Member for her works in establishing the system used to help the poor. She was the Society’s first Visitor and established the Relief Employment Committee that taught women domestic skills like sewing and needlework by employing them for seventy cents to a dollar per week making clothes for churches, orphanages, and other such organizations (Figure 15).[45] Kay worked to establish permanent offices for the group (Figure 17), eventually leading to the purchase of a property at 21 Harvey Street (Figure 16).[46] Sometime after the turn of the century, Kay ceased her work with the society after her health failed her, leaving her homebound until her death in 1914. Kay’s legacy and the methods she helped to develop lasted well into the twentieth century, until 1953 when the organization disbanded after eighty years of charity work.[47]

Pauline Temporary Home, 1880-1885

Kay’s work with the Germantown Relief Society put her in close contact with other causes and relief efforts such as those faced by children in almshouses. In 1879, Kay, along with several other men and women, organized the Pauline Temporary Home for Children, which opened its doors in 1880 across from the Germantown Hospital and Dispensary (Figure 18). Historically, men, women, and children were all housed in the same facilities in almshouses. Each group was treated in much the same way as the others and little thought was given to the welfare and care of the children. The main goal of the Pauline Temporary Home was to provide “a home for the poor children not otherwise properly provided for [in almshouses] until such time as their parents or friends shall be in a position to take care of them.” [48] More than anything, the Pauline Home sought to remove children “from the corrupting influence of the almshouse.”[49]

The Pauline Home was organized by the Guardians of the Poor but was run by the Women’s Auxiliary Board of the Germantown Relief Society, of which Kay was a key member. The Pauline Home was organized and maintained by a board of twenty-seven “lady managers” who cared for the children, maintained the facilities, and communicated with the Guardians of the Poor on admissions and discharges.[50] Upon its creation, Elizabeth Kay was one of the twelve founding incorporators who signed the charter and bylaws and she served on the first Board of Managers.[51] Kay, along with her duties on the Board of Managers, was the chairwoman of the standing committee on admission and discharge.[52]

The Board of Managers was composed of twenty-seven lady visitors who not only worked with the children in the Pauline Home proper but also worked with children who were housed in private, often wealthy households.[53] Women were seen to be the most obvious choice—even the only logical one—to operate the Home. “For self-evident reasons, this work must be performed in the main by women, whose innate tact, ready sympathy, and natural fondness for children prove them far superior to men”[54] As such, the majority of the founding members were women, and the Board of Managers was exclusively so.

Consequently, the moralizing element of Kay and the other female visitors is not to be overlooked. The organizers of the Pauline Home, in many ways, saw it their duty to provide instruction on responsibility and lessons in strong moral values to those in their care. While the nature of the Home was “temporary” as its name suggests, the female Board of Managers strived to reform each child while they were in the care of the Pauline Home. Each Sunday, the children were made to attend church at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in the morning, followed by Sunday School at the Somerville Mission School of the First Presbyterian Church.[55]

The children were provided access to public education and those that were too young to go to school attended kindergarten at the Pauline Home; the home retained a salaried teacher who instructed kindergarten. The Guardians of the Poor, in exchange for housing the children of almshouses, paid the Pauline Home through funds for operation and stipends for each child in their care. When the home first opened, they had too many beds and not enough children, so they reached out to almshouses outside of Germantown.[56]

By 1881, after just one year of operation, the Board of Managers reported that “there are now no children in the Germantown or Lower Dublin Poorhouses.”[57] The success of the Pauline Home and its diligent female board was evident. Only a few years later, the “temporary” nature of the Pauline Home proved evident. In 1885 the Home closed its doors permanently, after succeeding in their efforts to pass a law prohibiting children from almshouses.[58] The building on Penn Street, near the Germantown Hospital, was eventually sold and the remaining funding was transferred to the Children’s Aid Society which was seen to have “similar goals” and could “take up the work” of the Pauline Home’s legacy.[59]

Housing Children in Private Homes

In a speech published by WM L. Bull, a reformer, to the “directors and overseers of the poor, stewards of almshouses, and others” the author argued on behalf of the private home model, a new method for removing children from almshouses. He writes, “Home is the best, I might add [the] only proper place, for [children’s] true development.”[60] In its very early days, the Pauline Temporary Home did not have a permanent central location; rather, children were housed in the homes of well-off families and single women.

Housing children in private homes allowed for personalized love and was seen to teach children gratitude and responsibility, as charity was not simply given to them, they were active, contributing members of the family unit.[61] The family unit was the moralizer. Children had a need for affection and homes provided a much more stable environment for children to develop in. In the eyes of reformers like Kay, leaving children in almshouses only necessitated further problems, as “institutionalism breeds institutionalism.”[62]

Elizabeth Kay was among those who regularly housed children temporarily, doing so in her own house at 227 East High Street. In two separate federal censuses, Kay is noted to have “adopted daughters” living with her. Since she never married or had children, it can be inferred that these were likely children she housed temporarily. Perhaps of even more interest, is the fact that Kay started housing children in her home as far back as 1870, even before she lived at 227 East High Street. According to the 1870 census, Elizabeth Harper Kay lived at 5056 Germantown Avenue with her mother Elizabeth, and two younger girls Meta Kay and Charlotte Burroughs, both in school aged 18 and 8 respectively.[63] Ten years later in 1880, Elizabeth and her family still lived at 5056 Germantown Avenue, but the young children staying with her had changed. Meta and Charlotte were no longer living there, but Marcelle and Annie are listed as adopted daughters. Marcelle was from France and Annie was from Rhode Island, and they were one and eighteen respectively. While the Pauline Temporary Home was active in 1880, it is clear that Kay’s work with children extends much farther back, and perhaps influenced her work in shaping the creation of the Pauline Temporary Home.

Conclusion

Upon her death, Elizabeth Harper Kay left the property to her sister Florence Kay Stokes, who died that same year in October 1914.[64] Florence left the property to her daughters, maintaining the female line of Kay ownership. The daughter’s, in less than a year, sold the property to Dorothea Wiegner, listed as a dressmaker in the 1915 city directory.[65] Wiegner did not hold the property for long and later sold the property to Charles Snowden Rockey, one of the houses longest residents and first male owner. In 2006 the property was lost in a court case and was awarded to Fannie Mae before it was purchased by Charles Davis and sold to GELT Properties LLC, the current owner of the property. The family that rents the home are in the process of purchasing the home.[66]

The Elizabeth Harper Kay house represents a significant remaining work of architecture George T. Pearson and is representative of his eclectic designs that refused to conform to just one traditional style. As a landscape of patronage, High Street, and the Pearson houses on it are a significant example of the architects work and ability to play houses off of one another.

227 East High Street is significant as the home of Elizabeth Harper Kay, a celebrated charity worker whose role in shaping the charitable landscape of Germantown and Philadelphia is almost entirely unknown. Her life and works represent a much broader narrative of women in charity and philanthropy that is often altogether forgotten or obscured. Women like Kay had an immeasurable impact on the shaping and reform of society.

The Elizabeth Harper Kay house maintains excellent integrity and its narratives parallel the early rise of organized charity and philanthropy across the United States. As an example of women’s history and women’s roles in charity, there could not be a better example than 227 East High Street. Kay’s house was the lifelong base of operations for her charitable efforts and is clear tangible reflection of her life and charitable works.

Major Bibliographical References

“Biography Files, Philadelphia Architects and Building,” n.d. Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Bull, WML. “The Children of the Almshouses, What Shall We Do with Them? A Plea on Behalf of the Private Home Plan,” n.d. Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Wj. *422. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Germantown Relief Society. “Germantown Relief Society Records,” 1953 1873. Germantown Historical Society.

“Pauline Temporary Home, Germantown: First Annual Report, 1880: 3rd Report, 1883.” Philadelphia, 1881. Historical Society of Philadelphia.

“Pauline Temporary Home of Germantown: 1st to 3rd Annual Reports, 1880-1882: Charter and by-Laws, 1881.” Philadelphia, 1881. Historical Society of Philadelphia.

Pearson: A Biography, n.d. http://www.brynmawr.edu/cities/courses/05-306/proj2/jt2/Pearsonbio.htm.

“Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide,” May 10, 1886. The Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Rauch, Julia B. “Quakers and the Founding of the Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charitable Relief and Repressing Mendicancy.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 98, no. 4 (October 1974): 438–55.

____ “Women in Social Work: Friendly Visitors in Philadelphia, 1880.” Social Service Review 49, no. 2 (June 1975): 241–59.

Roydhouse, Marion W. Women of Industry and Reform. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical Association, 2007.

Scott M. Cutlip. Fund Raising in the United States: Its Role in America’s Philanthropy. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1965.

Spain, Daphne. How Women Saved the City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Watson, Frank Dekker. The Charity Organization Movement in the United States. New York: Arno Press & The New York Times, 1971.

Footnotes

[1] “Pearson: A Biography,” http://www.brynmawr.edu/cities/courses/05-306/proj2/jt2/Pearsonbio.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Graham, Charles,” Philadelphia Architects and Buildings, Athenaeum of Philadelphia, https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/463352.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Huttson, Addison,” Philadelphia Architects and Buildings, Athenaeum of Philadelphia, https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/25239.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Pearson: A Biography,” http://www.brynmawr.edu/cities/courses/05-306/proj2/jt2/Pearsonbio.html.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, May 10, 1886, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

[10] E. H. Butler to Elizabeth Gummey, Deed Book G.G.P. 62, p. 438 and following, City of Philadelphia Municipal Archives.

[11] Architectural Plans of 231 High Street, Germantown Historical Society; Boyd’s Philadelphia City Directory, 1885.

[12] “The Architecture of George T. Pearson, Part I,” http://www.brynmawr.edu/cities/archx/gtp/gtpto86.html.

[13] “Long in Relief Work: Robert Coulter has been superintendent of the Germantown Society since 1873 and has helped to develop a highly efficient system of charity work,” 1911, Box 1, Newspaper Clippings, Germantown Relief Society Papers, Germantown Historical Society.

[14] “Charity Graft Quickly Halted,” 1910, Box 1, Newspaper Clippings, Germantown Relief Society Papers, Germantown Historical Society.

[15] “Charity Worker Dead,” Elizabeth Harper Kay Obituary, 1914, Obituary Clippings, Germantown Historical Society.

[16] Elizabeth Harper Kay’s mother was also named Elizabeth Harper Kay. Since the younger never married, she retained her mother’s name for the entirety of her life. Unless referred to otherwise, any further references to Elizabeth Harper Kay will refer to the younger of the two, the daughter, who built the house in 1886.

[17] Halcyon, Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 23 June 1821, Record Group 36, Series M425, Roll 31. Records of the United States Custom Service, 1745-1997, The National Archives at Washington, D.C.

[18] “John Ippotsen Kay.” Find A Grave. Accessed October 18, 2017. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=141479826

[19] Boyd’s Philadelphia City Directory, 1885.

[20] 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Philadelphia Ward 22, District 72, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 17.

[21] 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Philadelphia Ward 22, Enumeration District 449, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 13.

[22] “Dwelling for Kay, Mrs.,” May 10, 1886. Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide, 208.

[23] 1900 U.S. Federal Census, Philadelphia Ward 22, Enumeration District 498, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 132A; 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Philadelphia Ward 22, Enumeration District 412, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2B.

[24] Marion W. Roydhouse, Women of Industry and Reform: Shaping the History of Pennsylvania, 1865-1940 (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Historical Society, 2007) 4-6.

[25] Ibid., 5.

[26] Ibid., 45.

[27] Frank Dekker Watson, The Charity Organization Movement in the United States (New York: Arno Press & The New York Times, 1971) 174.

[28] HSP Papers Read at the Fourth Congress of Women, Names and Addresses of Officers and Members of the Association for the Advancement of Women, 1877. Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *399.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Watson, The Charity Organization Movement, 176.

[32] Eleventh, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Annual Report of The Managers of the Germantown Dispensary and Hospital, 1881-1883, Hospitals Box 1, Germantown Historical Society.

[33] The Germantown Dispensary and Hospital Annual Report, 1918, Hospitals Box 1, Germantown Historical Society.

[34] The Germantown Dispensary and Hospital Seventh Annual, 1877, Hospitals Box 1, Germantown Historical Society.

[35] Watson, The Charity Organization Movement, 175.

[36] Ibid., 172.

[37] Ibid., 175

[38] Ibid., 175. Jessie McCulley, “The Germantown Relief Society: The First Society for Organizing Charity in the United States, 1873-1913,” Germantown Crier 48, (Spring 1998): 24-31.

[39] Watson, The Charity Organization Movement, 175.

[40] Watson, The Charity Organization Movement, 176.

[41] Julia B. Rauch, “Quakers and the Founding of the Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charitable Relief and Repressing Mendicancy,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 98, No. 4 (1974): 441.

[42] “Charity Worker Dead,” Elizabeth Harper Kay Obituary, 1914, Obituary Clippings, Germantown Historical Society.

[43] Jessie McCulley, “The Germantown Relief Society: The First Society for Organizing Charity in the United States the First Forty Years: 1873-1913,” The Germantown Crier 48, Spring (1998): 24-31.

[44] [Visitor Notebooks], Box 2, Germantown Relief Society Papers, Germantown Historical Society.

[45] Lilly H. Kay, “Report of the Relief Employment Committee,” Report of the Women’s Relief Society, 1875-1876 in Report of Germantown Relief Society 1874-1909, Germantown Historical Society.

[46] 21 Harvey Street is still extant today and is in a fairly good state of preservation when compared with the original photo of the building found in the Germantown Archives, see attached. Harvey Street is located opposite of High Street, along Germantown Avenue.

[47] Jessie McCulley, “The Germantown Relief Society: The First Society for Organizing Charity in the United States the First Forty Years: 1873-1913,” The Germantown Crier 48, Spring (1998): 24-31.

[48] Charter and Bylaws of the Pauline Temporary Home of Germantown, 1881, pamphlets boxes, Germantown Historical Society.

[49] First Annual Report of the Board of Managers of Pauline Temporary Home, 1880, Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *422.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid. Second Annual Report of the Board of Managers of Pauline Temporary Home, 1881, Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *422.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] WML Bull, “The Children of the Almshouses, What shall we do with them? A plea on behalf of the private home plan,” Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *422.

[55] Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *422.

[56] First Annual Report of the Board of Managers of Pauline Temporary Home, 1880, Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *399.

[57] Second Annual Report of the Board of Managers of Pauline Temporary Home, 1881, Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *422.

[58] Pamphlets Boxes, Pauline Temporary Home, Germantown Historical Society.

[59] After the disbanding of the Pauline Temporary Home in 1885, the transfer of funding to the Children’s Aid Society was hardly seamless. An ensuing court case between the Germantown Hospital, the Commonwealth, and the founders of the Pauline Home lasted until 1891 when the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania awarded the funding to the Children’s Aid Society. For further information, see Commonwealth v. Pauline Home, 1891.

[60] WML Bull, “The Children of the Almshouses,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *422.

[61] Ibid.

[62] WML Bull, “The Children of the Almshouses, What shall we do with them? A plea on behalf of the private home plan,” Philadelphia Secular Charities: Women, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Wj. *422.

[63] 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Philadelphia Ward 22, District 72, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 17.

[64] Deed Book E.L.T. 466, p. 570 and following, City of Philadelphia Municipal Archives.

[65] Boyd’s Philadelphia City Directory, 1885.

[66] For more information on the chain of title and other home owners see Appendix B.