anacostia park cultural landscape inventory

National Capital Parks—East, National Park Service, Washington, DC

Full Text Available: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2288081

Historical Overview

Although the area that encompassed the Anacostia Park cultural landscape did not exist as a permanent landscape until the 20th century, it is located in a region that has been inhabited by humans since at least 15,000 BCE (Louis Berger 2016: 6-8). English colonizer John Smith, who explored the Chesapeake watershed in 1608, recorded the location of a village near the mouth of the Anacostia River that he called Nacotchtank, meaning “at the trading town.” Other explorers quickly followed suit using Smith’s map, exacerbating tensions between Native American groups and White colonizers. Between 1608 and 1790, Europeans replaced Native Americans as the main inhabitants of the land that would eventually become Washington, D.C. European plantations relied on enslaved labor to cultivate cash crops such as tobacco, which was transported to market along the navigable waterways of the Eastern Branch of the Potomac River (now known as the Anacostia River). However, by 1762, agricultural runoff rendered much of the Eastern Branch too shallow for navigation, blocking portions of the Navy Yard channel. Due to this, the nature of agriculture shifted away from the cash-crop model towards smaller plots, as many of the larger landowners sold off portions of their land.

As heightened construction and poor agricultural practices resulted in runoff and deforestation, the shoreline of the Anacostia River transformed over the 19th century into large areas of marshy wetlands, dense grasses, and accumulated waste (Gutheim and Lee 2006: 147). Given the sedimentation of the Navy Yard channel portions and the Anacostia River’s associations with unsightly, unnavigable, and unhygienic conditions, engineers began designing for its reclamation. River improvements were underway by 1892 and continued in earnest after 1898 when Congress passed an act mandating the dredging of the Anacostia River. By the time the McMillan Plan of 1902 was published, District officials called for the construction of an "Anacostia Water Park” on the reclaimed banks of the river. Under such a plan, the river’s silt would be dredged and dumped on the Anacostia flats, after which the reclaimed land would be used for park purposes (Moore 1902: 105). “Anacostia Park” was officially named and established under an act of Congress in 1918.

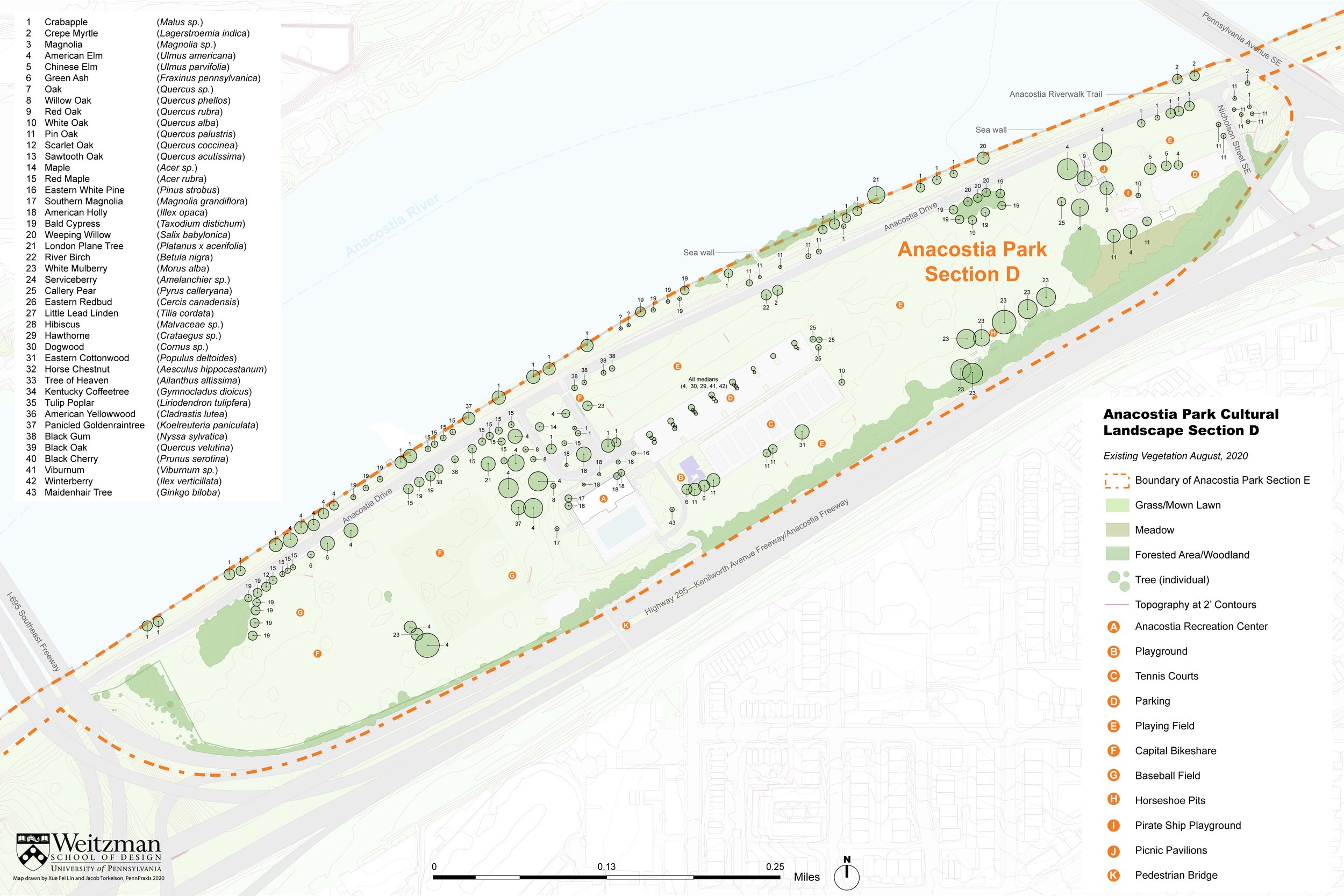

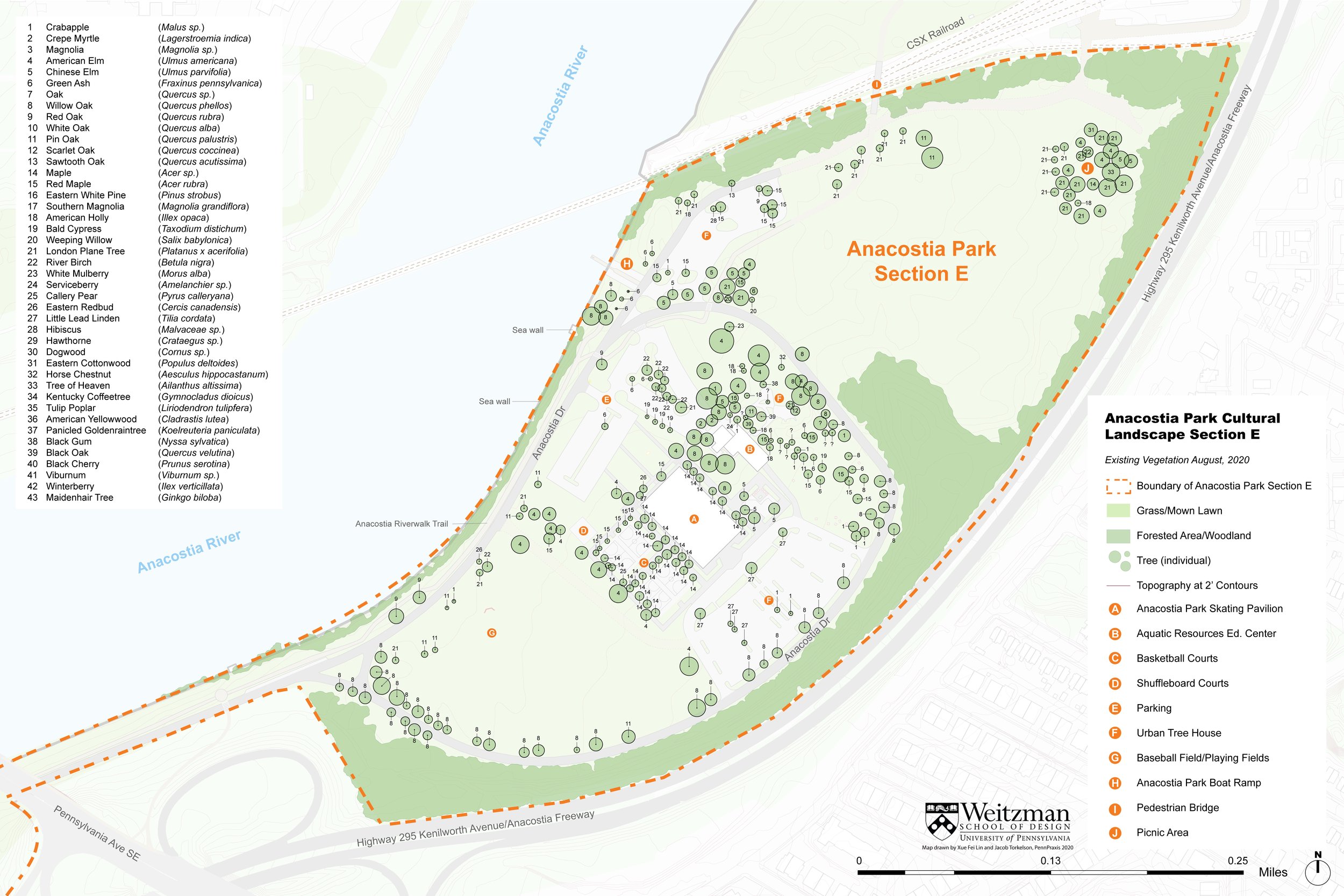

Reclamation efforts in the early 20th century precipitated recreational improvements under the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds (OPBG). The design and planning for the new Anacostia Park in Section D of the cultural landscape were in progress by 1922-1923, under landscape architects Irwin W. Payne and Thomas C. Jeffers. While Payne and Jeffers drew up plans for Anacostia Park Section D, work continued on the reclamation and construction of parkland in other sections, including Section E. The OPBG broke ground for Anacostia Park on August 2, 1923. Dredging and construction of the Anacostia Park cultural landscape were complete by 1924, with the construction of seawalls north of the cultural landscape finished by 1927. In 1925, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers transferred Section E to the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks (successor agency of the OPBG) to become part of the evolving park.

Section D of Anacostia Park was specifically envisioned as a segregated, White-only recreation area of a segregated Anacostia Park; Section C, meanwhile, was envisioned as the Black section of the park. As designed, the 11the Street Bridge would be the center of the park, dividing the two segregated sides. However, funding never materialized for the development of Section C, and much of it was given away to the District for tree nurseries. Despite the lack of recreational development in Section C, Payne wasted no time in further developing Section D of the cultural landscape. By 1930, Section D included a White-only nine-hole golf course, numerous sports fields, and a large clubhouse.

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, much of the country became unemployed and impoverished. Desperation and disgruntlement grew, particularly among those veterans of the recent world war who felt abandoned by their government. In May of 1932, thousands of unemployed World War I veterans and their families formed the Bonus Army to march on Washington and demand early cash redemption of their service certificates promised by Congress. The Bonus Army occupied the Anacostia flats in the unimproved Anacostia Park Section C for weeks. The temporary encampment consisted of impromptu shelters organized along a military grid. However, the Bonus Army camp was short-lived; after just a few weeks, on July 28th, 1932, U.S. military forces violently evicted the group without their bonuses.

After the hasty, forced departure of the Bonus Army, much of Section C of the cultural landscape lay in ruin. Under the New Deal, an economic recovery and employment program created by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, several groups worked at Anacostia Park to clean up the Bonus Army occupation and improve it as parkland. These groups included the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Public Works Administration (PWA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Under their tenure, these groups improved existing recreational facilities, established new facilities, graded the landscape, and planted new vegetation. Despite the rapid growth and development of the park system in Washington, D.C. in the first half of the 20th century, not all of the District’s residents enjoyed equal access to park facilities. Segregation continued to be the rule in Anacostia Park Sections C and D. The District-wide policy of segregated recreation also extended to military facilities in the District. On September 21, 1941, the first army recreation camp for Black soldiers in the District opened in Section C. The new facility for Black soldiers at Anacostia Park was the first of several such camps aimed at providing a safe place for Black soldiers to find recreation while on leave.

Despite the rapid growth and development of the park system in Washington, D.C. in the first half of the 20th century, not all of the District’s residents enjoyed equal access to park facilities. Segregation continued to be the rule in Anacostia Park Sections C and D. The District-wide policy of segregated recreation also extended to military facilities in the District. On September 21, 1941, the first army recreation camp for Black soldiers in the District opened in Section C. The new facility for Black soldiers at Anacostia Park was the first of several such camps aimed at providing a safe place for Black soldiers to find recreation while on leave.

In the summer of 1949, the Department of the Interior and District officials began to consider an end to the segregation of recreational facilities. However, before an agreement could be reached, a series of incidents between Black and White youth at the Anacostia Pool compelled the federal government to integrate public facilities, regardless of the District’s preferences. Skirmishes at the Anacostia Pool in Section D precipitated a change in policy that desegregated all public recreational facilities and eventually resulted in the full desegregation of public pools in the District in 1954.

In 1941, the beginning of U.S. involvement in World War II (WWII) dictated a rapid increase in the number of federal employees, which required a dramatic increase in available office space in Washington, D.C. The Naval Receiving Station (NRS) was established in Section C of Anacostia Park to serve as an expanded administrative and educational training facility for the nearby Navy Yard. After the conclusion of WWII, the NRS continued to occupy the site into the 1980s. However, the construction of the Anacostia Freeway (I-295) in 1959 resulted in the gradual removal of facilities and personnel from Section C. Between 1959-1980, all wartime structures in Section C were either demolished or transferred to the National Park Service (Dolph 2001: 10-12).

As construction on the Anacostia Freeway progressed in the 1950s and 1960s, the National Park Service was forced to close the Anacostia Golf Course. NPS officials used the closure of the golf course to create new plans for an expanded course that featured a driving range, 18 holes, a new miniature golf course, and a golf center (Babin 2017: 73). However, only the golf center was built in Section E in 1961; the redesigned course never reopened. By 1964, the Anacostia Freeway was complete and open to traffic, creating a physical barrier between Anacostia Park and the surrounding neighborhoods.

The last major improvement to the cultural landscape occurred between 1974-1976, when architects Keyes, Lethbridge, and Condon undertook a Bicentennial redesign of Section E and portions of Section D. The firm worked closely with the adjacent neighborhoods to design new park facilities. Responding to community input, the firm designed “park nodes” that provided small-scale recreational opportunities for residents. The principal of the project, Colden Florance, called for the complete redesign of Section E. The new plans centered around a large pavilion (later known as the skating center) that was designed to be flexible and open-air. The landscape around the pavilion included new plantings and sports facilities (Scott 1993: 276-77; Washington Post, January 9, 1977: K1).

Few significant changes have been made to the cultural landscape since the Bicentennial. Minor improvements and maintenance have been carried out by NPS officials throughout the study area. Since the period of significance, notable additions to the park include the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail and the new pirate ship playground near the Pennsylvania Avenue SE bridge. The cultural landscape retains integrity to all sub-periods of significance and is in fair condition.

SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY

This CLI recommends a single expansive period of significance in order to address Anacostia Park’s many areas of significance: pre-1668 to 1976. This period represents the significance of the Anacostia River landscape from the pre-colonial era to the Bicentennial, acknowledging the cultural landscape’s role in over three centuries of locally- and nationally-significant history in the District of Columbia.

This CLI recommends a single expansive period of significance that is further refined into sub-periods based on each criterion and area of significance. The period extends from pre-1668 to 1976, representing the history of the banks of the Anacostia River from the pre-colonial era to the National Park Service’s Bicentennial-era investments in the cultural landscape as a model for community-engaged design in federal parks. Within the larger period of significance, the CLI’s criteria and areas of significance recognize overlapping sub-periods associated with important movements and historical events, significant persons, significant architectural works, and the potential to yield significant archeological findings. The extended period of significance spans precontact with the Nacotchtank, European colonization, the subsequent displacement and dispossession of the Nacotchtanks, the 18th- and 19th-century development of the Anacostia region as part of the District of Columbia, the reclamation of the Anacostia River and its flats, the Bonus Army occupation, the 20th-century development of the Anacostia River flats for use as a park and recreation area, and the refinement of the cultural landscape design in response to community concerns.

This CLI recommends that the Anacostia Park cultural landscape’s significance be refined and expanded to encompass the following periods according to Criteria A, C, and D:

Criterion A

1890-1964, with local significance under Criterion A, for its role in the pattern of development for urban parks in Washington from the late 19th century to the 1960s;

1932, with national significance under Criterion A, as the site of the Bonus Army Encampment in one of the largest protests and occupations in the history of Washington, D.C.;

1932-1941, with local significance under Criterion A, for its role in the New Deal employment programs that undertook park rehabilitation projects in Anacostia Sections C and D;

1941-1949, with local significance under Criterion A, for its role in the desegregation of the military and public recreational facilities in the District of Columbia;

1942-1959, with local significance under Criterion A, having hosted a substantial temporary military reservation during WWII when many federal reservations were converted from recreational to wartime uses; and

1968-1976, with local significance under Criterion A, as a model for the National Park Service’s community-engaged approach to park programming and design in the late 20th century;

Criterion C

1890-1925, with local significance under Criterion C, as a significant recreational landscape that embodies the evolution of 19th and 20th-century park planning, construction, and landscape architecture;

Criterion D

Pre 1668-1890 and 1932, with local significance under Criterion D, for its potential to yield information about the prehistory and history of the Anacostia River Valley and its inhabitants, as well as the Bonus Army that historically occupied Section C in 1932.

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION SUMMARY AND CONDITION

This CLI finds that the Anacostia Park cultural landscape retains integrity based on the extant conditions that are consistent with its period of significance (with sub-periods of significance defined as pre-1668 to 1890; 1890-1925; 1890-1964; 1932; 1932-1941; 1941-1949; 1942-1959; 1968-1976). Original landscape characteristics and features from the period of significance remain in place at Anacostia Park, including its land use for passive and active recreation, flat topography, segmented composition, views of adjacent historic landmarks, Bicentennial planting scheme, and limited small-scale features. The landscape displays all seven aspects that determine integrity, as defined by the National Register of Historic Places.

[The Anacostia Park CLI was written by Jacob Torkelson under the supervision of Molly Lester as part of the Urban Heritage Project, an initiative of PennPraxis and the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. It was completed between 2019-2020 under a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Area, National Park Service]

Full Text Available: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2288081