fort drive cultural landscape inventory—fort slocum to fort totten component landscape

Rock Creek Park, National Park Service, Washington, DC

Full Text Available: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2288127

Historical Overview

The Fort Drive component cultural landscape was formally incorporated as part of the District of Colombia under surveyor Andrew Ellicott in 1792, although it wasn’t delineated or improved as a park until later periods. Until the mid-19th century, the cultural landscape remained primarily agricultural in use, with most parcels consisting of crops and forested areas. In 1763, William Dudley Digges patented ‘Chillum Castle Manor,’ which included 4,443 acres of land along the present-day boundary between the District of Columbia and Prince Georges County, Maryland. This included the cultural landscape, which was used as a large-scale cash-crop plantation and cultivated by enslaved laborers.

By the 1830s and 1840s, wealthy residents of Washington City began establishing ‘gentleman farms’ in the hills surrounding the city due to the rapid urbanization in Washington City and a resultant desire to escape its unhealthful conditions. Suburbanization in the Antebellum period was spurred by the expansion of the Washington City street grid and the establishment of throughways such as the 7th Street turnpike. At the advent of the Civil War, the cultural landscape was divided into four substantial estates, farms, and plantations. By 1861, the cultural landscape included buildings, structures, roadways, and vegetation associated with the Caroline Fairfax Sanders plantation, ‘Woodburne.’

The period between 1861-1865 marked one of the most substantial periods of development for the cultural landscape, as Union forces rapidly constructed the Civil War Defenses of Washington in the hills surrounding the city. Existing forests, fields, structures, and other landscape features were indiscriminately cleared to make way for the construction of defensive features. Forts Slocum and Totten (constructed north and south of the cultural landscape) were connected through the cultural landscape by rifle trenches built by Union forces; there are no apparent physical traces within the study area dating to this era.

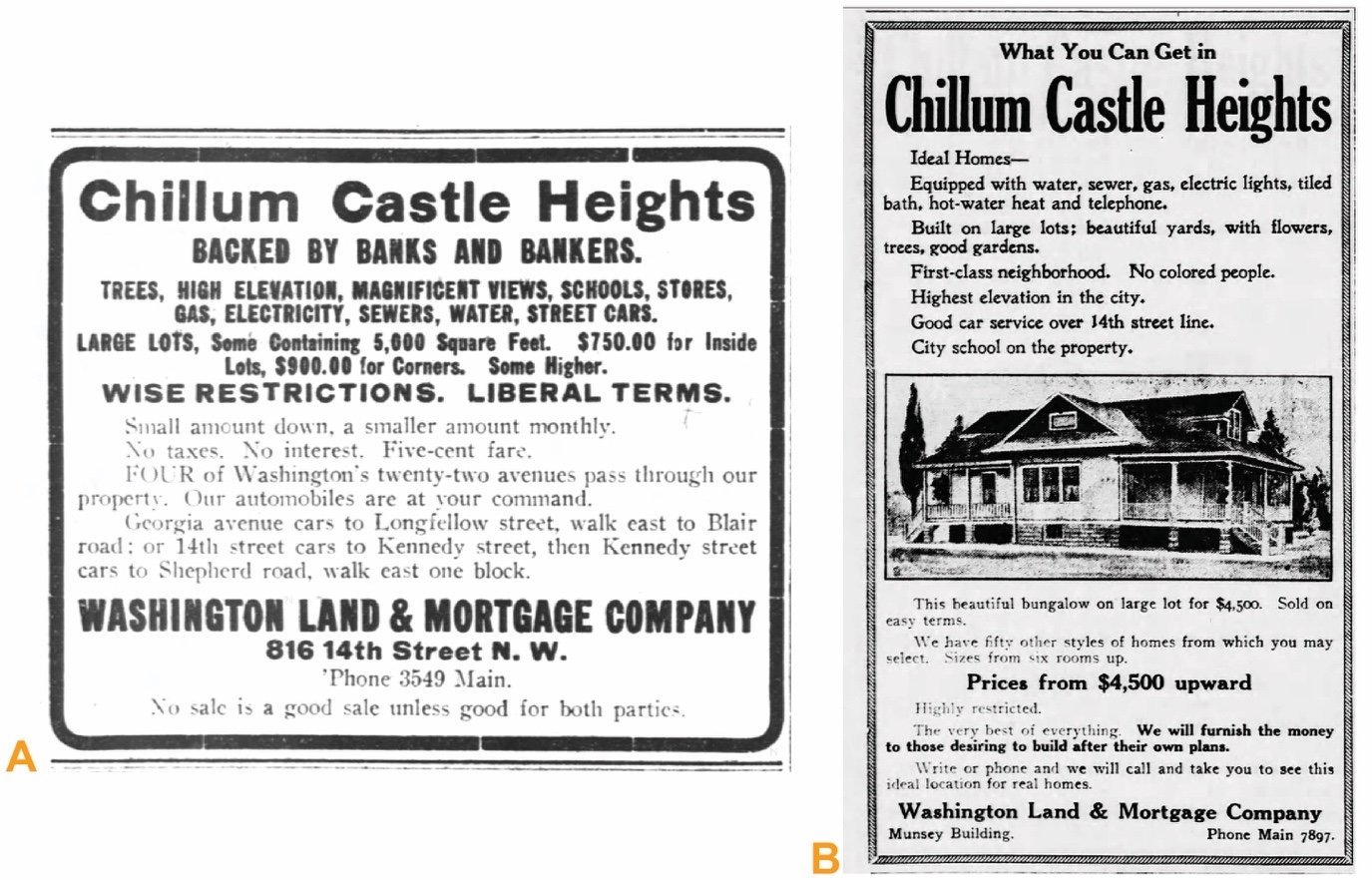

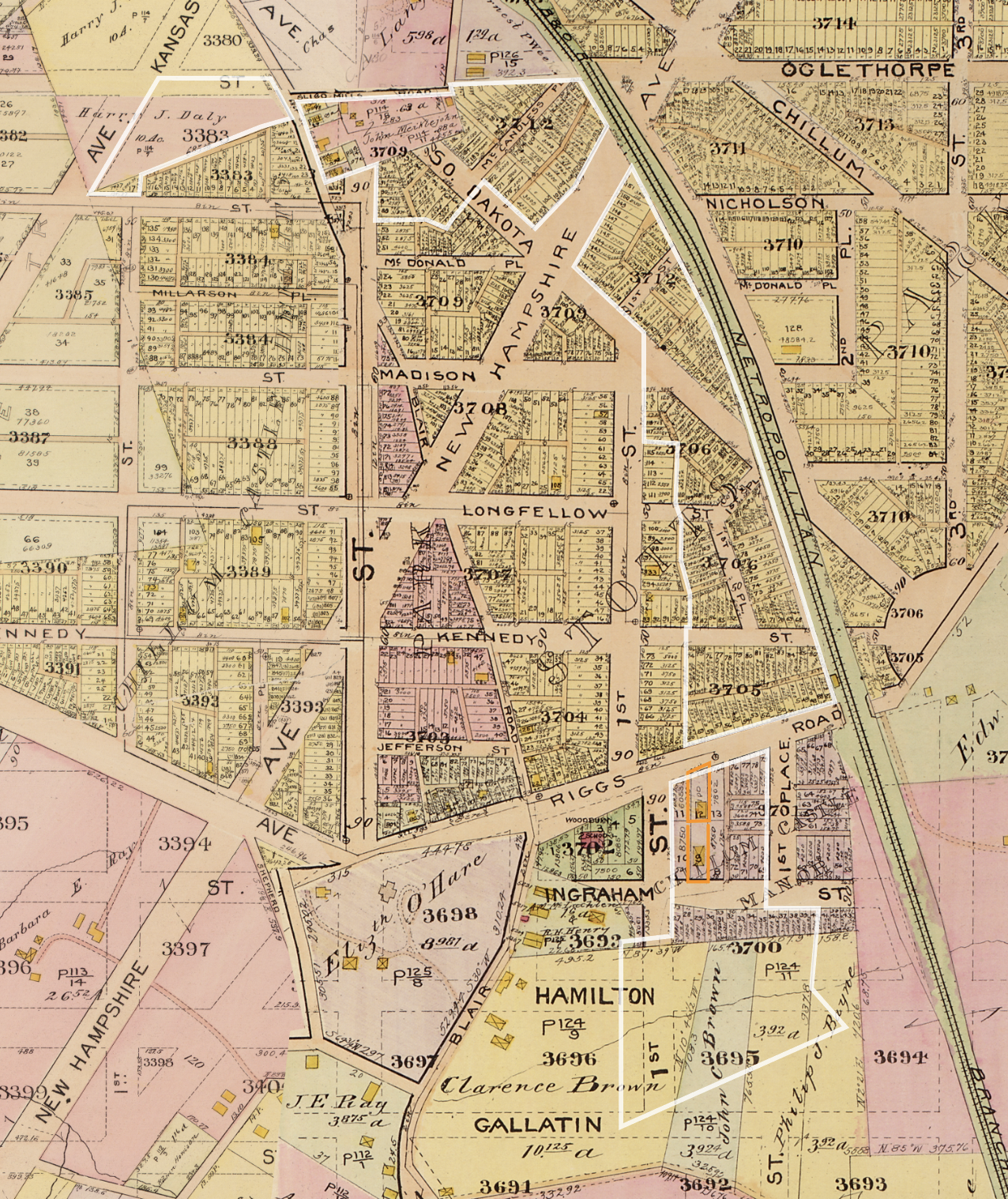

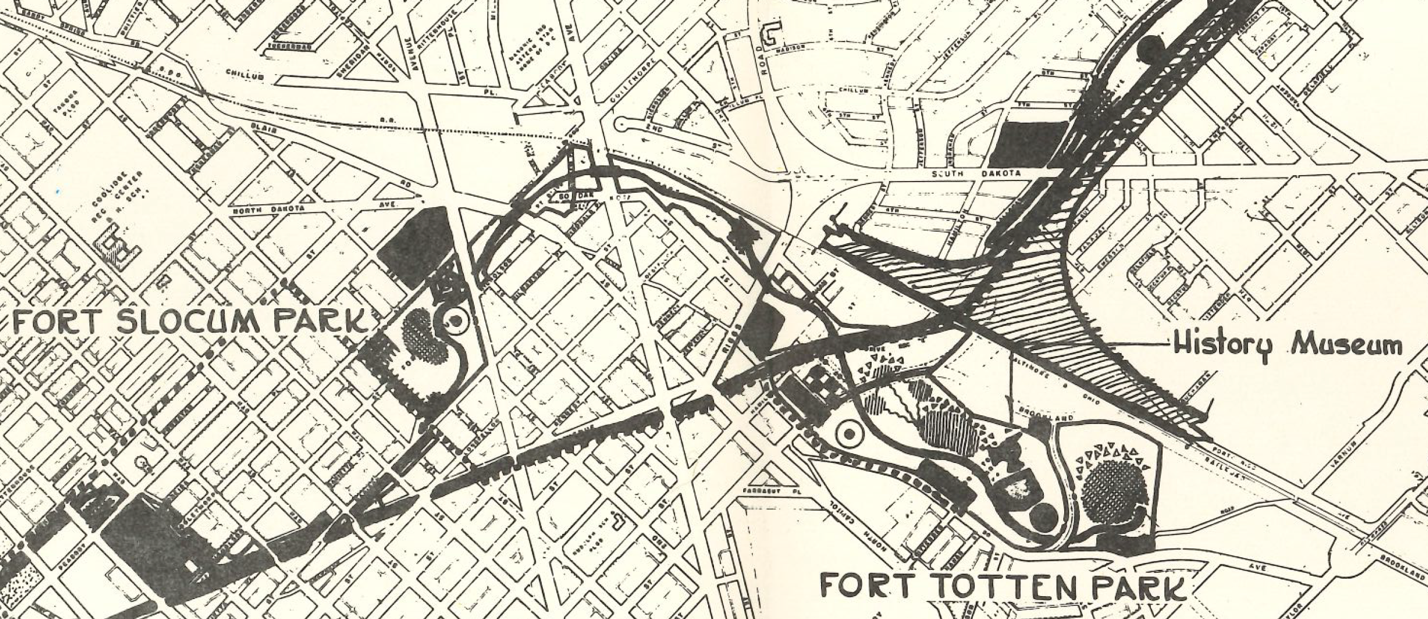

The postbellum era saw rapid suburbanization in the northern portions of the District. Private developers used racial covenants to bar anyone of color from settling in these new developments, including those platted within the boundaries of the cultural landscape. By the time the 1902 McMillan Plan was published, the cultural landscape had been almost entirely subdivided and prepared for residential development. Among its design tenets, the McMillan Plan proposed a parkway connecting the former fortifications encircling Washington. In 1927, Congress passed enabling legislation to create a parkway linking the Civil War-era fortifications and the rights-of-way between them.

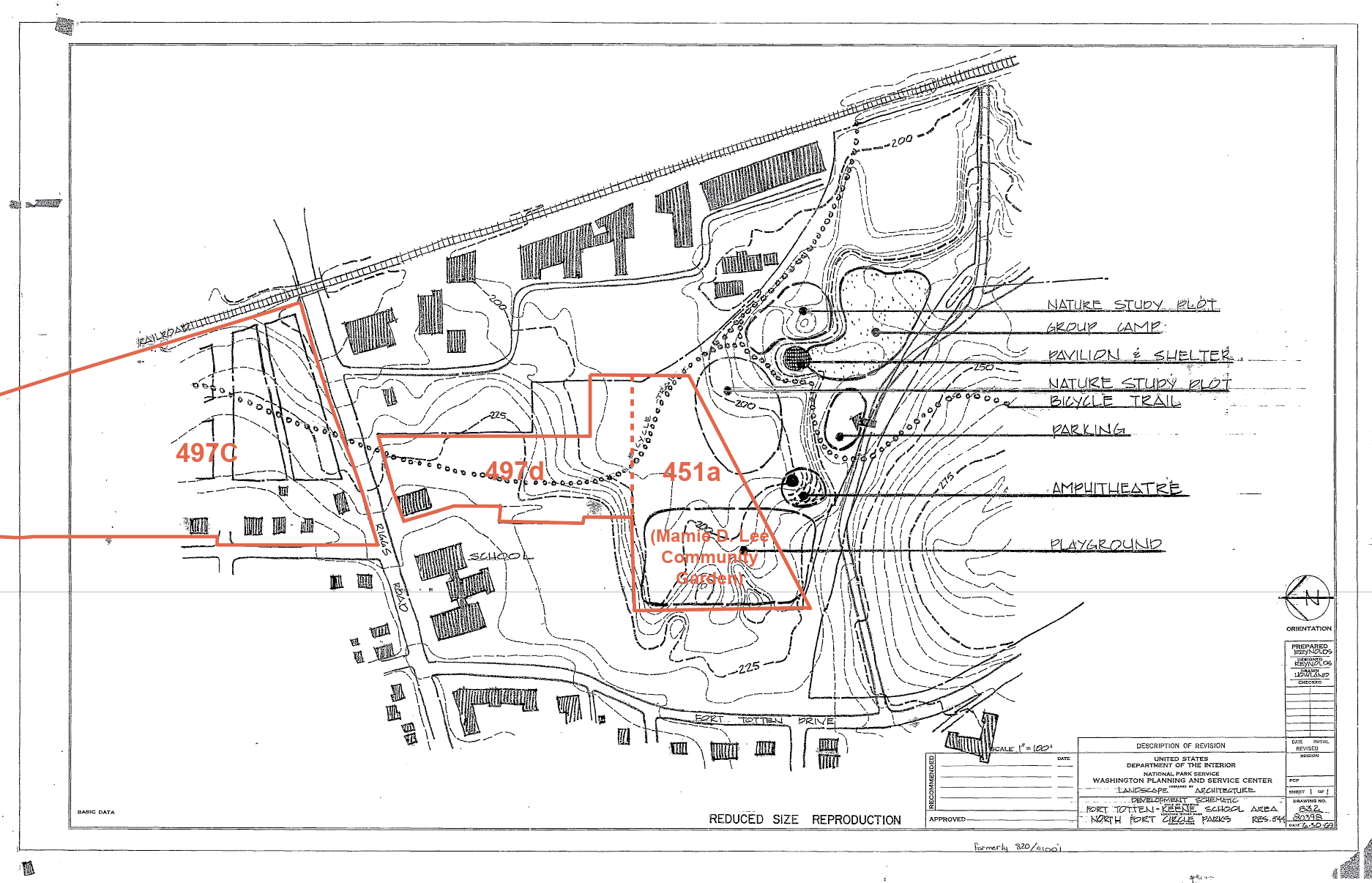

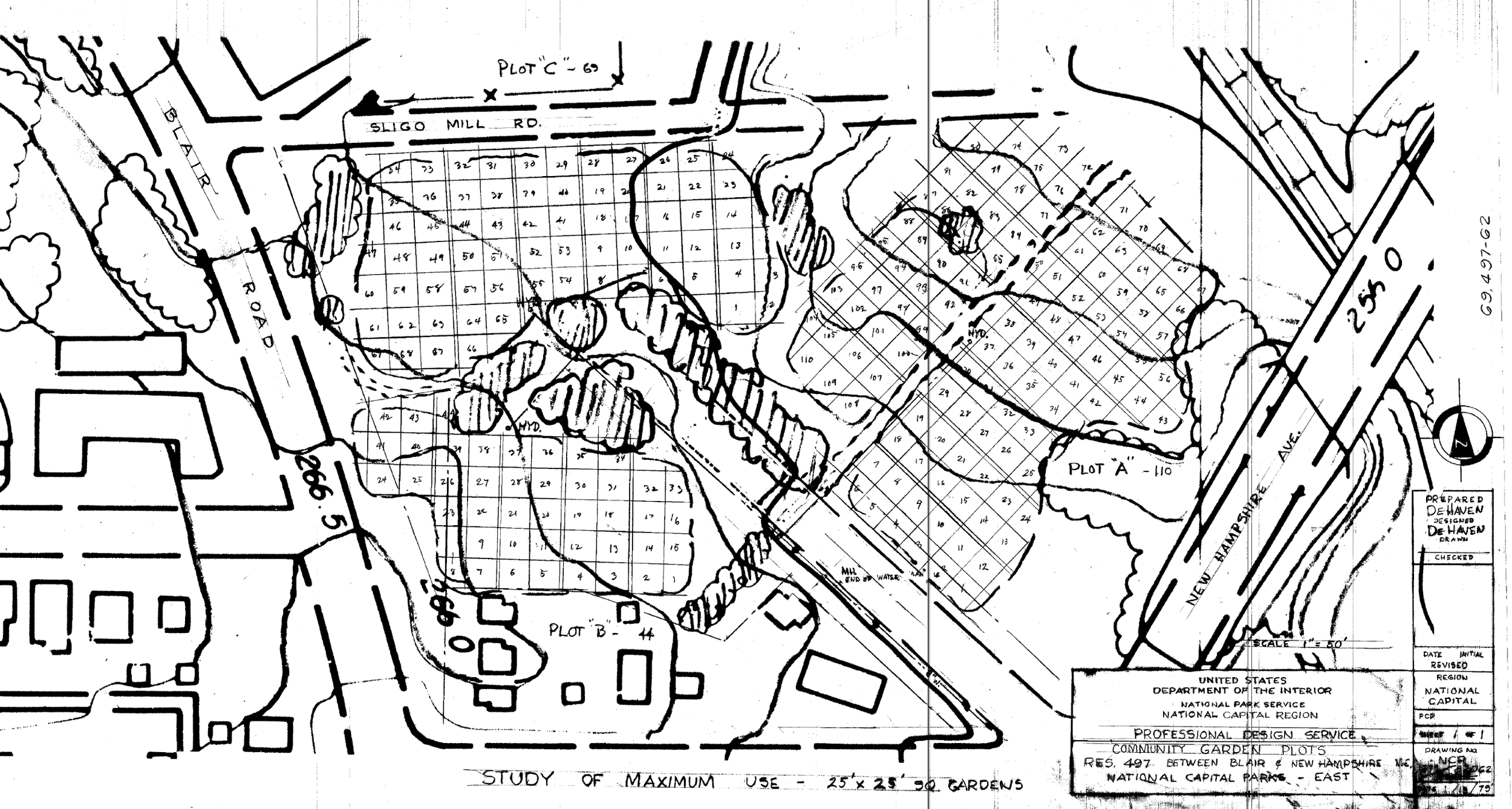

The passage of the 1930 Capper-Cramton Act provided much-needed funds for the acquisition of privately held lands for parkway purposes. However, even as the National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCPPC) proceeded to acquire the cultural landscape, the agency lacked the Congressional authority to develop the land. As the cultural landscape awaited improvement as a parkway, the American Women’s Voluntary Services (AWVS) established a victory garden at the northern end of the cultural landscape in order to aid in the war effort during World War II. This garden has remained in continual use since World War II and now operates as the Blair Road Community Garden. By 1968, thwarted by decades of failed large-scale proposals, the National Park Service (NPS) and NCPPC abandoned the idea of Fort Drive as a parkway and shifted instead to preserving the land as an urban greenbelt. This was codified in the 1968 Fort Circle Parks Master Plan; the cultural landscape, however, saw little to no direct improvement under the plan. The last major change to the cultural landscape occurred in the mid to late 1970s, when the Mamie D. Lee School and Community Garden were established on the southern end of the cultural landscape.

SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY

The Fort Drive component cultural landscape derives local significance as a segment of parkland acquired for the development of Fort Drive and, later, the Fort Circle Parks. The cultural landscape was previously included in the National Register of Historic Places draft nomination for the Civil War Defenses of Washington/Fort Circle Parks [Additional Documentation and Boundary Increase, 2015], with significance based on Criteria A, C, and D. The period of significance for that draft nomination is 1861-1972. This CLI recommends that the Fort Drive component cultural landscape’s significance be refined to encompass the following two periods:

1930-1968, with local significance under Criterion A, based on the reservation’s association with the development of the Fort Drive and Fort Circle Parks, beginning with its earliest acquisition in 1930 under the Capper-Cramton Act and ending with the adoption of the 1968 Fort Circle Parks Master Plan;

1942-1945, with local significance under Criteria A, based on the Blair Road Community Garden’s association as a victory garden established within the cultural landscape during World War II.

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION SUMMARY AND CONDITION

This CLI finds that the Fort Drive component cultural landscape retains integrity based on the extant conditions that are consistent with its periods of significance (1930-1968; 1942-1945). Original landscape characteristics and features from the periods of significance remain in place in the study area, including its use as passive park and greenway, natural rolling topography, bifurcated and segmented composition, internal views within the community gardens, agricultural plantings in the community gardens and mature vegetation throughout, and several small-scale features (including those associated with the community gardens). The landscape displays all seven aspects that determine integrity, as defined by the National Register of Historic Places.

Map of the site boundaries for the Fort Drive—Fort Slocum to Fort Totten component cultural landscape. (Map by Xue Fei Lin and CLI author, 2020)

[The Fort Drive component CLI was written by Jacob Torkelson under the supervision of Molly Lester as part of the Urban Heritage Project, an initiative of PennPraxis and the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. It was completed between 2019-2020 under a cooperative agreement with the National Capital Area, National Park Service]

Full Text Available: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2288127